Dr. V.K.Maheshwari, M.A. (Socio, Phil) B.Sc. M. Ed, Ph.D.

Former Principal, K.L.D.A.V.(P.G) College, Roorkee, India

Mrs Sudha Rani Maheshwari, M.Sc (Zoology), B.Ed.

Former Principal, A.K.P.I.College, Roorkee, India

Marriage is neither heaven nor hell, it is simply purgatory.

To regulate the relation of sexes is the first task of those customs that constitute the moral code of a group. Actually these are a perennial source of discord, violence, and possible degeneration. The basic form of this sexual regulation is marriage, which may be defined as the association of mates for the care of offspring. This institution is quite a fluctuating and variable institution, which has passed through almost every conceivable form and experiment in the course of its history, from the primitive care of offspring without the association of mates to the modern association of mates without the care of offspring.

Marriage- its biological origins

Our animal forefathers invented it. Some birds seem to live as reproducing mates in a divorceless monogamy. Among gorillas and orang-utans the association of the parents continues to the end of the breeding season and has many human features. Any approach to lose behaviour on the part of the female is severely punished by the male.(1) Marriage is older than man.

Societies without marriage are rare, but the sedulous inquirer can find enough of them to form a respectable transition from the promiscuity of the lower mammals to the marriages of primitive men. In Futuna and Hawaii many people did not marry at all;(2) the Lubus mated freely and indiscremately, and had no conception of marriage; certain tribes of Borneo lived in marriageless association, freer than the birds; and among some peoples of primitive Russia “the men utilized the women without distinction, so that no woman had her appointed husband. African pygmies have been described as having no marriage institutions but as following” their animal instinct wholly without restraint”(3) This primitive “nationalization of women”, corresponding to primitive communism in land and food, passed away at so early a stage that few traces of it remain. Some memory of it, however, lingered on in divers forms: in the feeling of many nature peoples that monogamy- which they would define as the monopoly of a woman by one man- is unnatural and immoral; in periodic festivals of license when sexual restraints were temporarily abandoned; in the demand that a woman should give herself- as at the Temple of Mylitta (one of the forms of Ishtar) in Babylon- to any man that solicited her, before she would be allowed to marry, in the custom of wife-lending, so essential to many primitive codes of hospitality; or right of the first night, by which, in early feudal Europe, the lord of the manor, perhaps representing the ancient rights of the tribe, occasionally deflowered the bride before the bridegroom was allowed to consummate the marriage.(4)

Sexual Communism in Marriage

A variety of tentative unions gradually took the place of indiscriminate relations. Among the Orang Sakai of Malacca a girl remained for a time with each man of the tribe, passing from one to another until she had made the rounds; then she began again.(5) Among the Yakuts of Siberia, the Botocudos of South Africa, the lower classes of Tibet, and many other peoples, marriage was quite experimental and could be ended at the will of either party, with no reasons given or required. Among the Bushmen” any disagreement sufficed to end a union, and new connections could immediately be found for both.” Among the Damaras, according to Sir Francis Galton, “the spouse was changed almost weekly, and I seldom knew without inquiry who the pro tempore husband of each lady was at any particular time.” Among the Balia “women are bandied about from man to man, and of their own accord leave one husband for another. Young women scarcely out of their teens often have had four or five husbands, all still living.” (6) The original word for marriage, in Hawaii meant to try.”(7)

Marco Polo writes of a Central Asiatic tribe, inhabiting Peyn (now Keriya) in the 13th century: “If a married man goes to a distance from home to be absent twenty days, his wife has a right, if she is so inclined to take another husband and the men on the same principle, marry wherever they happen to reside.”(8) So old are the latest innovations in marriage and morals.

Individual Marriage

What was it that led men to replace the semi-promiscuity of primitive society with individual marriage? Since, in a great majority of nature peoples, there are few, if any, restraints on premarital relations, it is obvious that physical desire does not give rise to the institution of marriage. For marriage, with its restrictions and psychological irritations, could not possibly compete with sexual communism as a mode of satisfying the erotic propensities of men. Nor could the individual establishment offer at the outset any mode of rearing children that would be obviously superior to their rearing by the mother, her family, and the clan. Some powerful economic motives must have favoured the evolution of marriage. In all probability these motives were connected with the rising institution of property.

Individual marriage came through the desire of the male to have cheap slaves, and to avoid bequeathing his property to other men”s children. Polygamy, or the marriage of one person to several mates, appears here and there in the form of polyandry- the marriage of one woman to several men-as among the Todas and some tribes of Tibet;(9) the custom may still be found where males outnumber females considerably.(10) But this custom soon falls prey to the conquering male, and polygamy has come to mean for us, usually, what would more strictly be called polygyny- the possession of several wives by one man. In early society, because of hunting and war, the life of the male is more violent and dangerous, and the death rate of men is higher, than that of women. The consequent excess of women compels a choice between polygamy and the barren celibacy of a minority of women; but such celibacy is intolerable to peoples who require a high birth rate to make up for a high death rate, and who therefore scorn the mate-less and childless woman. Again , men like variety; as the Negroes of Angola expressed it, they were “ not able to eat always of the same dish.” Also, men like youth in their mates, and women age rapidly in primitive communities. The women themselves often favoured polygamy; it permitted them to nurse their children longer and therefore to reduce the frequency of motherhood without interfering with the erotic and philoprogenitive inclinations of the male. Some times the first wife, burdened with toil, helped her husband to secure an additional wife, so that the burden might be shared and additional children might raise the productive power and wealth of the family.(11) Children were economic assets, and men invested in wives in order to draw children from them like interest. In the patriarchal system wives and children were in effect the slaves of the man; the more a man had of them, the richer he was. The poor man practised monogamy, but he looked upon it as a shameful condition, from which some day he would rise to the respected position of a polygamous male.

Polygamy in Marriage

Doubtless polygamy was well adapted to the marital needs of a primitive society in which women out numbered men. It had a eugenic value superior to that of contemporary monogamy; for where as in modern society the most able and prudent men marry latest and have least children, under polygamy the most able men, presumably, secured the bests mates and had most children. Hence polygamy has survived among practically all nature people, even among the majority of civilized mankind; only in our day has it begun to die in the orient. Certain conditions, however, militated against it. The decrease in danger and violence, consequent upon a settled agricultural life, brought the sexes towards an approximate numerical equality; and under these circumstances open polygamy, even in primitive societies become the privilege of the prosperous minority.(12) The mass of the people practised a monogamy tempered with adultery, while another minority, of willing or regretful celibates, balanced the polygamy of the rich .Jealousy in the male, and possessiveness in the female, entered into the situation more effectively as the sexes approximated in number; for where the strong could not have a multiplicity of wives except by taking the actual or potential wives of other men, and by offending their own polygamy became a difficult matter, which only the cleverest could manage. As property accumulated, and men were loath to scatter it in small bequest, it became desirable to differentiate wives into “chief wife” and concubines, so that only the children of the former should share the legacy; this remained the status of marriage in Asia until our own generation. Gradually the chief wife became the only wife, the concubines became kept women in secret and apart, or they disappeared; and as Christianity entered upon the scene, monogamy, in Europe, took the place of polygamy as the lawful and outward form of sexual association. But monogamy, like letters and the state, is artificial, and belongs to the history, not to the origins, of civilization.

Exogamy in Marriage

Exogamy is a social arrangement where marriage is allowed only outside of a social group. The social groups define the scope and extent of exogamy, and the rules and enforcement mechanisms that ensure its continuity.

Whatever form the union might take, marriage was obligatory among nearly all primitive peoples. The unmarried male had no standing in the community, or was considered only half a man.(13) Exogamy, too was compulsory: that is to say, a man was expected to secure his wife from another clan than his own. Whether this custom arose because the primitive mind suspected the evil effects of close inbreeding or because such intergroup marriages created or cemented useful political alliances, promoted social organization, and lessened the danger of war, or because the capture of a wife from another tribe had become a fashionable mark of male maturity, or because familiarity breeds contempt and distance lends enchantment to the view- we do not know. In any case restriction was well-nigh universal in early society.

Marriage by service

How did the male secure his wife from another tribe? Where the matriarchal organization was strong he was often required to go and live with the clan of the girl whom he sought. As the patriarchal system developed the suitor was allowed after a term of service to the father, to take his bride back to his own clan. Some times the suitor shortened the matter with plain, blunt force. It was an advantage as well as a distinction to have stolen a wife; not only would she be a cheap slave, but new slaves could be begotten of her, and these children would chain her to her slavery.

Marriage by Capture

Sometimes the women were included in the spoils of war. The slavs of Russia and Serbia practised occasional marriage by capture until the last century.(14) Vestiges of it remain in the custom of simulating the capture of the bride by the groom in certain wedding ceremonies.(15) All in all it was a logical aspect of the almost incessant war of tribes, and a logical starting-point for the eternal war of the sexes whose only truces are brief nocturnes and dreamless sleep.

Marriage by purchase

As wealth grew it became more convenient to offer the father a substantial present-or a sum of money- for his daughter, rather than serve for her in an alien clan or risk the violence and feuds that might come of marriage by capture. Consequently marriage by purchase and parental arrangement was the rule of the early societies.(16) Transition forms occur; the Melanesians sometimes stole their wives, but made the theft legal by a later payment to his family. Among some natives of New Guinea the man abducted the girl, and then, while he and she were in hiding, commissioned his friends to bargain with her father over a purchase price.(17) The ease with which moral indignation in these matters might be financially appeased is illuminating.

Marriage by purchase prevails throughout primitive Africa, and is still a normal institution in China and Japan; it flourished in ancient India and Judea, and in pre-Columbian Central Amarica and Peru; instances of it occur in Europe today.(18) A Maori mother wailing loudly, bitterly cursed the youth who had eloped with her daughter, until he presented her with a blanket.”That was all I wanted,” she said; “I only wanted to get a blanket, and therefore made this noise.”(19) Usually the bride cost more than a blanket: among the Hottentots her price was an ox or a cow; among the Croo three cows and a sheep; among the Kaffirs six to thirty head of cattle, depending upon the rank of the girl’s family; and among Togas sixteen dollars cash and six dollars in goods.(20) It is a natural development of patriarchal institutions; the father owns the daughter, and may dispose of her, within broad limits, as he sees fit. The Orinoco Indians expressed the matter by saying that the suitor should pay the father for rearing the girl for his use.(21) Sometimes the girl was exhibited to potential suitors in a bride –show; so among the Somalis the bride, richly caparisoned, was led about on horseback or on foot in an atmosphere heavily perfumed to stir the suitors to a handsome price.(22) There is no record of women objecting to marriage by purchase; on the contrary, they took keen pride in the sums paid for them and scorned the woman who gave herself in marriage without a price;(23)they believed that in a “love –match” the villainous male was getting too much for nothing.(24) On the other hand, it was usual for the father to acknowledge the bride-groom’s payment with a return gift which, as time went on approximated more and more in value to sum offered for the bride.(25) Rich fathers, anxious to smooth the way for their daughters, gradually enlarged these gifts until the institution of the dowry took form; and the purchase of the husband by the father replaced, or accompanied, the purchase of the wife by the suitor.(26)

Primitive Love in Marriage

In all these forms and varieties of marriage there is hardly a trace of romantic love. We find a few cases of love-marriages among the Papuans of New Guinea; among other primitive peoples we come upon instances of love ( in the sense of mutual devotion rather than mutual need) , but usually these attachments have nothing to do with marriage. In simple days men married for cheap labor, profitable percentage, and regular meals. “In Yariba,” says Lander, “marriage is celebrated by the natives as unconcernedly as possible; a man thinks as little of taking a wife as of cutting an ear of corn-affection is altogether out of question.”(27) Since premarital relations are abundant in primitive society, passion is not dammed up by denial, and seldom affects the choice of a wife.. For the same reason-the absence of delay between desire and fulfilment-no time is given for that brooding introversion of frustrated, and therefore idealizing, passion which is usually the source of youthful romantic love. Primitive peoples are too poor to be romantic. One rarely finds love poetry in their songs. The kiss, which seems so indispensable now, is quite unknown to primitive peoples, or known only to be scorned.

Economic Functions of Marriage

In general the “savage” takes his sex philosophically, with hardly more of metaphysical misgivings than the animal; he does not brood over it, or fly into a passion with it; it is as much a matter of course with him as his food. He makes no pretence to idealistic motives. Marriage is never a sacrament with him, and seldom an affair of lavish ceremony; it is frankly a commercial transaction. It never occurs to him to be ashamed that he subordinates emotional to practical considerations in choosing his mate; he would rather be ashamed of the opposite, and would demand of us, if he were as immodest as we are, some explanation of our custom of binding a man and a woman together almost for life because sexual desire has chained them for a moment with its lightning. The primitive male looked upon marriage in terms of sexual license but of economic cooperation. He expected the woman-and the woman expected herself-to be not so much gracious and beautiful as useful and industrious, she was to be an economic asset rather than a total loss; otherwise the matter- of- fact “savage” would never have thought of marriage at all. Marriage was a profitable partnership, not a private debauch; it was a way whereby a man and a woman working together, might be more prosperous than if each worked alone. Wherever, in the history of civilization, woman has ceased to be an economic asset in marriage, marriage has decayed; and sometimes civilization has decayed with it.

*************************************************************************************

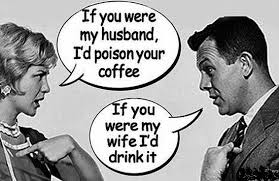

Present Scenario (JUST FOR FUN )

BEFORE MARRIAGE

He: Yes. At last. It was so hard to wait.

She: Do you want me to leave?

He: NO! Don’t even think about it.

She: Do you love me?

He: Of course! Over and over!

She: Have you ever cheated on me?

He: NO! Why are you even asking?

She: Will you kiss me?

He: Every chance I get!

She: Will you hit me?

He: Are you crazy! I’m not that kind of person!

She: Can I trust you?

He: Yes.

She: Darling!

AFTER MARRIAGE

Read from the bottom going up

- Unknown

*************************************************************************************

References

1-Ellis,H., Studies in psychology of sex vi 422

2-Briffault,Robert:The Mothers ii 154

3-Sumner and Keller,iii1547

4-Muller-Lyer, Family55

5- Sumner and Keller,iii1548

6- Briffault,Robert:The Mothers ii 81

7-Lubbock, Sir John- The Origin of Civilization 69

8- Polo Marco- Travels 70

9-Examples in Briffault i 769

10- Westermarck-Moral ideas i 387

11- Muller-Lyer- Modern Marriage 34

12- Lowie, R.H- Are we civilized? 128

13- Sumner and Keller,iii1540, Westermarck-Moral ideas i 399

14- Westermarck-Moral ideas i 435 – Sumner and Keller,iii1625-6

15- Sumner and Keller,iii1631

16-Hobhouse,L.T: Morals in Evolution 15817-

17- Sumner and Keller,iii1629

18- Westermarck-Moral ideas i 383

19- Briffault,Robert:The Mothers ii 244

20- Muller-Lyer- Modern Marriage 125

21- Hobhouse,L.T: Morals in Evolution 151-

22-Ibid- 1648

23- Briffault,Robert:The Mothers ii 219-21

24- Lowie, R.H- Are we civilized? 125

25 Briffault,Robert:The Mothers ii 215

26- Sumner and Keller,iii1658

27- Lubbock, Sir John- The Origin of Civilization 52