Dr. V.K.Maheshwari, M.A. (Socio, Phil) B.Sc. M. Ed, Ph.D.

Former Principal, K.L.D.A.V.(P.G) College, Roorkee, India

Mrs Sudha Rani Maheshwari, M.Sc (Zoology), B.Ed.

Former Principal. A.K.P.I.College, Roorkee, India

Civilizations are the generations of the racial soul. As family-rearing, and then writing, bound the generations together, handing down the lore of the dying to the young, so print and commerce and a thousand ways of communication may bind the civilizations together, and preserve for future cultures all that is of value for them in our own. Let us, before we die, gather up our heritage, and offer it to our children.

In one important sense the “savage,” too, is civilized, for he carefully transmits to his children the heritage of the tribe that complex of economic, political, mental and moral habits and institutions which it has developed in its efforts to maintain and enjoy itself on the earth. It is impossible to be scientific here; for in calling other human beings “savage” or “barbarous” we may be expressing no objective fact, but only our fierce fondness for ourselves, and our timid shyness in the presence of alien ways.

Doubtless we underestimate these simple peoples, who have so much to teach us in hospitality and morals; if we list the bases and constituents of civilization we shall find that the naked nations invented or arrived at all but one of them, and left nothing for us to add except embellishments and writing. Perhaps they, too, were once civilized, and desisted from it as a nuisance. We must make sparing use of such terms as “savage” and “barbarous” in referring to our “contemporaneous ancestry.” Preferably we shall call “primitive” all tribes that make little or no provision for un-productive days, and little or no use of writing. In contrast, the civilized may be defined as literate providers.

Primitive improvidence

The moment man begins to take thought of the morrow he passes out of the Garden of Eden into the vale of anxiety; the pale cast of worry settles down upon him, greed is sharpened, property begins, and the good cheer of the “thoughtless” native disappears. The American Negro is making this transition today. “Of what are you thinking?” Peary asked one of his Eskimo guides. “I do not have to think,” was the answer; “I have plenty of meat.” Not to think unless we have to there is much to be said for this as the summation of wisdom.

“Three meals a day are a highly advanced institution. Savages gorge themselves or fast.” The wilder tribes among the American Indians considered it weak-kneed and unseemly to preserve food for the next day.” The natives of Australia are incapable of any labour whose reward is not immediate; every Hottentot is a gentleman of leisure; and with the Bush- men of Africa it is always “either a feast or a famine.” There is a mute wisdom in this improvidence, as in many “savage” ways.

Nevertheless, there were difficulties in this carelessness, and those organisms that outgrew it came to possess a serious advantage in the struggle for survival. The dog that buried .the bone which even a canine appetite could not manage, the squirrel that gathered nuts for a later feast, the bees that filled the comb with honey, the ants that laid up stores for a rainy day these were among the first creators of civilization. It was they, or other subtle creatures like them, who taught our ancestors the art of providing for tomorrow out of the surplus of today, or of preparing for winter in summer’s time of plenty.

Beginnings of provision- Hunting and fishing

Hunting is now to most of us a game, whose relish seems based upon some mystic remembrance, in the blood, of ancient days when to hunter as well as hunted it was a matter of life and death. With what skill those ancestors ferreted out, from land and sea, the food that was the basis of their simple societies! They grubbed edible things from the earth with bare hands; they imitated or used the claws and tusks of the animals, and fashioned tools out of ivory, bone or stone; they made nets and traps and snares of rushes or fibre, and devised innumerable artifices for fishing and hunting their prey. The Polynesians had nets a thousand ells long, which could be handled only by a hundred men; in such ways economic provision grew hand in hand with political organization, and the united quest for food helped to generate the state. The Tlingit fisherman put upon his head a cap like the head of a seal, and hiding his body among the rocks, made a noise like a seal; seals came toward him, and he speared them with the clear conscience of primitive war. Many tribes threw narcotics into the streams to stupefy the fish into cooperation with the fishermen; the Tahitians, for example, put into the water an intoxicating mixture prepared from the butco nut or the hora plant; the fish, drunk with it, floated leisurely on the surface, and were caught at the anglers’ will. Australian natives, swimming under water while breathing through a reed, pulled ducks beneath the surface by the legs, and gently held them there till they were pacified. The Tarahumaras caught birds by stringing kernels on tough fibres half buried under the ground; the birds ate the kernels, and the Tarahumaras ate the birds.”

Hunting was not merely a quest for food, it was a war for security and mastery, a war beside which all the wars of recorded history are but a little noise. In the jungle man still fights for his life, for though there is hardly an animal that will attack him unless it is desperate for food or cornered in the chase, yet there is not always food for all, and sometimes only the fighter, or the breeder of fighters, is allowed to eat. We see in our museums the relics of that war of the species in the knives, clubs, spears, arrows, lassos, bolas, lures, traps, boomerangs and slings with which primitive men won possession of the land, and prepared to transmit to an ungrateful posterity the gift of security from every beast except man. Even today, after all these wars of elimination, how many different populations move over the earth! Sometimes, during a walk in the woods, one is awed by the variety of languages spoken there, by the myriad species of insects, reptiles, carnivores and birds; one feels that man is an interloper on this crowded scene, that he is the object of universal dread and endless hostility.

Hunting and fishing were not stages in economic development, they were modes of activity destined to survive into the highest forms of civilized society. Once the centre of life, they are still its hidden foundations; behind our literature and philosophy, our ritual and art. We do our hunting by proxy, not having the stomach for honest killing in the fields; but our memories of the chase linger in our joyful pursuit of anything weak or fugitive, and in the games of our children even in the word game. In the last analysis civilization is based upon the food supply. The cathedral and the capitol, the museum and the concert chamber, the library and the university are the facade; in the rear are the shambles.

Herding- The domestication of animals

To live by hunting was not original; if man had confined himself to that he would have been just another carnivore. He began to be human when out of the uncertain hunt he developed the greater security and continuity of the pastoral life. For this involved advantages of high importance: the domestication of animals, the breeding of cattle, and the use of milk. We do not know when or how domestication began perhaps when the helpless young of slain beasts were spared and brought to the camp as playthings for the children.’ The animal continued to be eaten, but not so soon; it acted as a beast of burden, but it was accepted almost democratically into the society of man; it became his comrade, and formed with him a community of labour and residence. The miracle of reproduction was brought under control, and two captives were multiplied into a herd. Animal milk released women from prolonged nursing, lowered infantile mortality, and provided a new and dependable food. Population increased, life became more stable and orderly, and the mastery of that timid parvenu, man, became more secure on the earth.

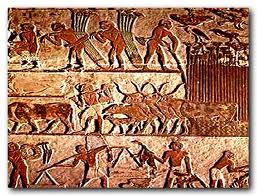

Agriculture

Meanwhile woman was making the greatest economic discovery of all the bounty of the soil. While man hunted she grubbed about the tent or hut for whatever edible things lay ready to her hand on the ground. In Australia it was understood that during the absence of her mate on the chase the wife would dig for roots, pluck fruit and nuts from the trees, and collect honey, mushrooms, seeds and natural grains. Even today, in certain tribes of Australia, the grains that grow spontaneously out of the earth are harvested without any attempt to separate and sow the seed; the Indians of the Sacramento River Valley never advanced beyond this stage.”

We shall never discover when men first noted the function of the seed, and turned collecting into sowing; such beginnings are the mysteries of history, about which we may believe and guess, but cannot know. It is possible that when men began to collect implanted grains, seeds fell along the way between field and camp, and suggested at last the great secret of growth. The Juangs threw the seeds together into the ground, leaving them to find their own way up. The natives of Borneo put the seed into holes which they dug with a pointed stick as they walked the fields. 9 The simplest known culture of the earth is with this stick or “digger.” In Madagascar fifty years ago the traveller could still see women armed with pointed sticks, standing in a row like soldiers, and then, at a signal, digging their sticks into the ground, turning over the soil, throwing in the seed, stamping the earth flat, and passing on to another furrow.

The second stage in complexity was culture with the hoe: the digging stick was tipped with bone, and fitted with a crosspiece to receive the pressure of the foot. When the Conquistadores arrived in Mexico they found that the Aztecs knew no other tool of tillage than the hoe. With the domestication of animals and the forging of metals a heavier implement could be used; the hoe was enlarged into a plough, and the deeper turning of the soil revealed a fertility in the earth that changed the whole career of man. Wild plants were domesticated, new varieties were developed, old varieties were improved.

Finally nature taught man the art of provision, the virtue of prudence, the concept of time. Watching woodpeckers storing acorns in the trees, and the bees storing honey in hives, man conceived perhaps after millenniums of improvident savagery the notion of laying up food for the future.

He found ways of preserving meat by smoking it, salting it, freezing it; better still, he built granaries secure from rain and damp, vermin and thieves, and gathered food into them for the leaner months of the year.

Slowly it became apparent that agriculture could provide a better and steadier food supply than hunting. With that realization man took one of the three steps that led from the beast to civilization speech, agriculture, and writing.

Food Cooking

It is not to be supposed that man passed suddenly from hunting to tillage. Many tribes, like the American Indians, remained permanently becalmed in the transition the men given to the chase, the women tilling the soil. Not only was the change presumably gradual, but it was never complete. Man merely added a new way of securing food to an old way; and for the most part, throughout his history, he has preferred the old food to the new. We picture early man experimenting with a thousand products of the earth to find, at much cost to his inward comfort, which of them could be eaten safely; mingling these more and more with the fruits and nuts, the flesh and fish he was accustomed to, but always yearning for the booty of the chase. Primitive peoples are ravenously fond of meat, even when they live mainly on cereals, vegetables and milk.” If they come upon the carcass of a recently dead animal the result is likely to be a wild debauch. Very often no time is wasted on cooking; the prey is eaten raw, as fast as good teeth can tear and devour it; soon nothing is left but the bones. Whole tribes have been known to feast for a week on a whale thrown up on the shore.” Though the Fuegians can cook, they prefer their meat raw; when they catch a fish they kill it by biting it behind the gills, and then consume it from head to tail without further ritual.”

The uncertainty of the food supply made these nature peoples almost literally omnivorous: shellfish, sea urchins, frogs, toads, snails, mice, rats, spiders, earthworms, scorpions, moths, centipedes, locusts, caterpillars, lizards, snakes, boas, dogs, horses, roots, lice, insects, larvae, the eggs of rep- tiles and birds there is not one of these but was somewhere a delicacy, to primitive men. u Some tribes are expert hunters of ants; others dry insects in the sun and then store them for a feast; others pick the lice out of one another’s hair, and eat them with relish; if a great number of lice can be gathered to make a petite marmite ,they are devoured with shouts of joy, as enemies of the human race. The menu of the lower hunting tribes hardly differs from that of the higher apes. ”

The discovery of fire limited this indiscriminate voracity, and cooperated with agriculture to free man from the chase. Cooking broke down the cellulose and starch of a thousand plants indigestible in their raw state, and man turned more and more to cereals and vegetables as his chief reliance. At the same time cooking, by softening tough foods, reduced the need of chewing, and began that decay of the teeth which is one of the insignia of civilization.

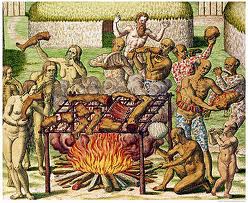

Cannibalism

To all the varied articles of diet that we have enumerated, man added the greatest delicacy of all his fellowman. Cannibalism was at one time practically universal; it has been found in nearly all primitive tribes, and among such later peoples as the Irish, the Iberians, the Picts, and the eleventh-century Danes.” Among many tribes human flesh was a staple of trade, and funerals were unknown. In the Upper Congo living men, women and children were bought and sold frankly as articles of food; on the island of New Britain human meat was sold in shops as butcher’s meat is sold among ourselves; and in some of the Solomon Islands human victims, preferably women, were fattened for a feast like pigs. The Fuegians ranked women above dogs because, they said, “dogs taste of otter.” In Tahiti an old Polynesian chief explained his diet to Pierre Loti: ‘The white man, when well roasted, tastes like a ripe banana.” The Fijians, however, complained that the flesh of the whites was too salty and tough, and that a European sailor was hardly fit to eat; a Polynesian tasted better.”

As far as the origin of this practice, there is no surety that the custom arose, as formerly supposed, out of a shortage of other food; if it did, the taste once formed survived the shortage, and became a passionate predilection. Everywhere among nature peoples blood is regarded as a delicacy never with horror; even primitive vegetarians take to it with gusto. Human blood is constantly drunk by tribes otherwise kindly and generous; sometimes as medicine, sometimes as a rite or covenant, often in the belief that it will add to the drinker the vital force of the victim.” No shame was felt in preferring human flesh; primitive man seems to have recognized no distinction in morals between eating men and eating other animals. In Melanesia the chief who could treat his friends to a dish of roast man soared in social esteem. “When I have slain an enemy,” explained a Brazilian philosopher-chief, “it is surely better to eat him than to let him waste. . . . The worst is not to be eaten, but to die; if I am killed it is all the same whether my tribal enemy eats me or not. But I could not think of any game that would taste better than he would. . . . You whites are really too dainty.”"

Doubtless the custom had certain social advantages. It anticipated Dean Swift’s plan for the utilization of superfluous children, and it gave the old an opportunity to die usefully. There is a point of view from which funerals seem an unnecessary extravagance. To Montaigne it appeared more barbarous to torture a man to death under the cover of piety, as was the mode of his time, than to roast and eat him after he was dead. We must respect one another’s delusions.

Someday, perhaps, these chattering quadrupeds, these ingratiating centipedes, these insinuating bacilli, will devour man and all his works, and free the planet from this marauding biped, these mysterious and unnatural weapons, these careless feet!-

Will Durant

REFERANCES:

BRIFFAULT, ROBERT: The Mothers. 3V. New York, 1927.

HAYES, E. C.: Introduction to the Study of Sociology. New York, 1918.

LIPPERT, JULIUS: Evolution of Culture. New York, 1931.

MASON, O. T.: Origins of Invention. New York, 1899.

MULLER-LYER,F.: History of Social Development. New York, 1921.

RATZEL, F.: History of Mankind. 2v. London, 1896.

RENARD, G.: Life and Work in Prehistoric Times. New York, 1929.

SPENCER, HERBERT: Principles of Sociology. 3V. New York, 1910.

SUMNER, W. G. and KELLER, A. G.: Science of Society. 3V. New Haven, 1928.

SUTHERLAND, G. A., ed.: A System of Diet and Dietetics. New York, 1925.

THOMAS, W.I. : Source Book for Social Origins. Boston, 1909.

WESTERMARCK, E.: Origin and Development of the Moral Ideas. 2V. Lon-

don, 1917-24.

WILL DURANT. : Our Oriental Heritage. Simon and Schuster. New York, 1954