Dr. V.K.Maheshwari, M.A(Socio, Phil) B.Sc. M. Ed, Ph.D

Former Principal, K.L.D.A.V.(P.G) College, Roorkee, India

Primitive communism is a concept originating from Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels that hunter-gather societies of the past practiced forms of communism. In Marx’s model of socioeconomic structures, societies with primitive communism had no hierarchical social class structures or capital accumulation.

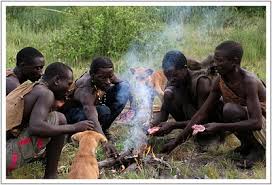

Frederick Engels ,in 1884 he described what human society was like “before class divisions arose”, writing, “Everything runs smoothly without soldiers, gendarmes or police, without nobles, kings, governors, prefects or judges, without prisons, without trials”. “There can be no poor and needy—the communistic household… know their responsibility towards the aged, the sick and those disabled in war… All are free and equal, including the women.”For most of human history people lived in very small groups, hunting and gathering food. Few archaeological remains have survived.

Engels called this pre-class society “primitive communism”

There were three main phases in human history, called (using the 19th century language) savagery, barbarism and civilisation. During the first two phases of savagery and barbarism, society was largely organised around kinship rather than economic relationships.

We are told that competition and division are hard-wired into humanity, evidence from pre-history points in the opposite direction.

These societies are not characterised by permanent leaders either. In the 1970s, an anthropologist asked a member of another hunter-gatherer people, the !Kung of Botswana, if they had chiefs. He replied, “Of course we have headmen! In fact, we are all headmen, each one of us is headman over himself.” “Leaders” among the !Kung had no real authority. They could persuade, but not enforce their opinions. At different times in hunter-gatherer societies, individuals take on leading roles, but this tends to be temporary, based on their ability at navigation, hunting or similar skills.The Hadza people are a community of hunter-gatherers who live in northern Tanzania. A classic study of their lives showed that in times past the Hadza worked on average less than two hours a day collecting food.

So for hundreds of thousands of years our ancestors lived lives that were more communal and more equal than today.

However, at a specific point in human history this changed. This occurred with the rise of class society. The old ways of organising society were transformed. We are a revolutionary species. We were born in complete equality and fraternity. There were no social classes, there was no state, there was no filth, there was no war. Those were our origins, but this was all lost with the neolithic revolution.

Trade was the great disturber of the primitive world, for until it came, bringing money and profit in its wake, there was no property, and there- fore little government. In the early stages of economic development property was limited for the most part to things personally used; the property sense applied so strongly to such articles that they (even the wife) were often buried with their owner; it applied so weakly to things not personally used that in their case the sense of property, far from being innate, required perpetual reinforcement and inculcation.

Almost everywhere, among primitive peoples, land was owned by the community. The North American Indians, the natives of Peru, the Chittagong Hill tribes of India, the Borneans and South Sea Islanders seem to have owned and tilled the soil in common, and to have shared the fruits together. “The land,” said the Omaha Indians, “is like water and wind what cannot be sold.” In Samoa the idea of selling land was unknown prior to the coming of the white man. Professor Rivers found communism in land still existing in Melanesia and Polynesia; and in inner Liberia it may be observed today.

Only less widespread was communism in food. It was usual among “savages” for the man who had food to share it with the man who had none, for travellers to be fed at any home they chose to stop at on their way, and for communities harassed with drought to be maintained by their neighbors. 88 If a man sat down to his meal in the woods he was expected to call loudly for some one to come and share it with him, before he might justly eat alone. When Turner told a Samoan about the poor in London the “savage” asked in astonishment: “How is it? No food? No friends? No house to live in? Where did he grow? Are there no houses belonging to his friends?” The hungry Indian had but to ask to receive; no matter how small the supply was, food was given him if he needed it; “no one can want food while there is corn anywhere in the town.” Among the Hottentots it was the custom for one who had more than others to share his surplus till all were equal. White travellers in Africa before the advent of civilization noted that a present of food or other valuables to a “black man” was at once distributed; so that when a suit of clothes was given to one of them the donor soon found the recipient wearing the hat, a friend the trousers, another friend the coat. The Eskimo hunter had no personal right to his catch; it had to be divided among the inhabitants of the village, and tools and provisions were the common property of all. The North American Indians were described by Captain Carver as “strangers to all distinctions of property, except in the articles of domestic use. .. . They are extremely liberal to each other, and supply the deficiencies of their friends with any superfluity of their own.” “What is extremely surprising,” reports a missionary, “is to see them treat one another with a gentleness and consideration which one does not find among common people in the most civilized nations. This, doubt- less, arises from the fact that the words ‘mine’ and ‘thine,’ which St. Chrysostom says extinguish in our hearts the fire of charity and kindle that of greed, are unknown to these savages.” “I have seen them,” says another observer, “divide game among themselves when they sometimes had many shares to make; and cannot recollect a single instance of their falling into a dispute or finding fault with the distribution as being unequal or otherwise objectionable. They would rather lie down themselves on an empty stomach than have it laid to their charge that they neglected to satisfy the needy. . . . They look upon themselves as but one great family.”

Why did this primitive communism disappear as men rose to what we, with some partiality, call civilization? Sumner believed that communism proved un-biological, a handicap in the struggle for existence; that it gave insufficient stimulus to inventiveness, industry and thrift; and that the failure to reward the more able, and punish the less able, made for a levelling of capacity which was hostile to growth or to successful competition with other groups. Loskiel reported some Indian tribes of the northeast as “so lazy that they plant nothing themselves, but rely entirely upon the expectation that others will not refuse to share their produce with them. Since the industrious thus enjoy no more of the fruits of their labor than the idle, they plant less every year.” Darwin thought that the perfect equality among the Fuegians was fatal to any hope of their becoming civilized; or, as the Fuegians might have put it, civilization would have been fatal to their equality.

Communism brought a certain security to all who survived the diseases and accidents due to the poverty and ignorance of primitive society; but it did not lift them out of that poverty. Individualism brought wealth, but it brought, also, insecurity and slavery; it stimulated the latent powers of superior men, but it intensified the competition of life, and made men feel bitterly a poverty which, when all shared it alike, had seemed to oppress none.( Perhaps one reason why communism tends to appear chiefly at the beginning of civilizations is that it flourishes most readily in times of dearth, when the common danger of starvation fuses the individual into the group. When abundance comes, and the danger subsides, social cohesion is lessened, and individualism increases; communism ends where luxury begins. As the life of a society becomes more complex, and the division of labor differentiates men into diverse occupations and trades, it becomes more and more unlikely that all these services will be equally valuable to the group; inevitably those whose greater ability enables them to perform the more vital functions will take more than their equal share of the rising wealth of the group. Every growing civilization is a scene of multiplying inequalities; the natural differences of human endowment unite with differences of opportunity to produce artificial differences of wealth and power; and where no laws or despots suppress these artificial inequalities they reach at last a bursting point where the poor have nothing to lose by violence, and the chaos of revolution levels men again into a community of destitution.

Hence the dream of communism lurks in every modern society as a racial memory of a simpler and more equal life; and where inequality or insecurity rises beyond sufferance, men welcome a return to a condition which they idealize by recalling its equality and forgetting its poverty. Periodically the land gets itself redistributed, legally or not, whether by the Gracchi in Rome, the Jacobins in France, or the Communists in Russia; periodically wealth is redistributed, whether by the violent confiscation of property, or by confiscatory taxation of incomes and bequests. Then the race for wealth, goods and power begins again, and the pyramid of ability takes form once more; under whatever laws may be enacted the abler man manages somehow to get the richer soil, the better place, the lion’s share; soon he is strong enough to dominate the state and rewrite or interpret the laws; and in time the inequality is as great as before. In this aspect all economic history is the slow heart-beat of the social organism, a vast systole and diastole of naturally concentrating wealth and naturally explosive revolution.)

Communism could survive more easily in societies where men were always on the move, and danger and want were ever present. Hunters and herders had no need of private property in land; but when agriculture became the settled life of men it soon appeared that the land was most fruitfully tilled when the rewards of careful husbandry accrued to the family that had provided it. Consequently since there is a natural selection of institutions and ideas as well as of organisms and groups the passage from hunting to agriculture brought a change from tribal property to family property; the most economical unit of production became the unit of ownership. As the family took on more and more a patriarchal form, with authority centralized in the oldest male, property became increasingly individualized, and personal bequest arose. Frequently an enterprising individual would leave the family haven, adventure beyond the traditional boundaries, and by hard labour reclaim land from the forest, the jungle or the marsh; such land he guarded jealously as his own, and in the end society recognized his right, and another form of individual property began. As the pressure of population increased, and older lands were exhausted, such reclamation went on in a widening circle, until, in the more complex societies, individual ownership became the order of the day. The invention of money cooperated with these factors by facilitating the accumulation, transport and transmission of property. The old tribal rights and traditions reasserted themselves in the technical owner-ship of the soil by the village community or the king, and in periodical redistributions of the land; but after an epoch of natural oscillation between the old and the new, private property established itself definitely as the basic economic institution of historical society.

Agriculture, while generating civilization, led not only to private property but to slavery. In purely hunting communities’ slavery had been unknown; the hunter’s wives and children sufficed to do the menial work. The men alternated between the excited activity of hunting or war, and the exhausted lassitude of satiety or peace. The characteristic laziness of primitive peoples had its origin, presumably, in this habit of slowly recuperating from the fatigue of battle or the chase; it was not so much laziness as rest. To transform this spasmodic activity into regular work two things were needed: the routine of tillage, and the organization of labour.

Such organization remains loose and spontaneous where men are working for themselves; where they work for others, the organization of labour depends in the last analysis upon force. The rise of agriculture and the inequality of men led to the employment of the socially weak by the socially strong; not till then did it occur to the victor in war that the only good prisoner is a live one. Butchery and cannibalism lessened, slavery grew. It was a great moral improvement when men ceased to kill or eat their fellowmen, and merely made them slaves. A similar development on a larger scale may be seen today, when a nation victorious in war no longer exterminates the enemy, but enslaves it with indemnities. Once slavery had been established and had proved profitable, it was extended by condemning to it defaulting debtors and obstinate criminals, and by raids undertaken specifically to capture slaves. War helped to make slavery, and slavery helped to make war.

Probably it was through centuries of slavery that our race acquired its traditions and habits of toil. No one would do any hard or persistent work if he could avoid it without physical, economic or social penalty. Slavery became part of the discipline by which man was prepared for industry. Indirectly it furthered civilization, in so far as it increased wealth and for a minority created leisure. After some centuries men took it for granted; Aristotle argued for slavery as natural and inevitable, and St. Paul gave his benediction to what must have seemed, by his time, a divinely ordained institution.

Gradually, through agriculture and slavery, through the division of labor and the inherent diversity of men, the comparative equality of natural society was replaced by inequality and class divisions. “In the primitive group we find as a rule no distinction between slave and free, no serfdom, no caste, and little if any distinction between chief and followers.” Slowly the increasing complexity of tools and trades subjected the unskilled or weak to the skilled or strong; every invention was a new weapon in the hands of the strong, and further strengthened them in their mastery and use of the weak. ( So in our time that Mississippi of inventions which we call the Industrial Revolution has enormously intensified the natural inequality of men. ) .Inheritance added superior opportunity to superior possessions, and stratified once homogeneous societies into a maze of classes and castes. Rich and poor became disruptively conscious of wealth and poverty; the class war began to run as a red thread through all history; and the state arose as an indispensable instrument for the regulation of classes, the protection of property, the waging of war, and the organization of peace.

REFERENCES:

BRIFFAULT, ROBERT: The Mothers. 3V. New York, 1927.

BUCHER, KARL: Industrial Evolution. New York, 1901.

HOBHOUSE, L.T.: Morals in Evolution. New York, 1916.

KROPOTKIN,PETER.: Mutual Aid. New YORK 1917

LIPPERT, JULIUS: Evolution of Culture. New York, 1931.

LUBBOCK, SIR JOHN: The Origin of Civilization. London, 1912.

MASON, O. T.: Origins of Invention. New York, 1899.

SUMNER, W. G. and KELLER, A. G.: Science of Society. 3V. New Haven, 1928.

WILL DURANT: Our Oriental Heritage. Simon and Schuster. New York 1954