Dr. V.K.Maheshwari, M.A(Socio, Phil) B.Sc. M. Ed, Ph.D

Former Principal, K.L.D.A.V.(P.G) College, Roorkee, India

Mankind has always been interested in dreams, and many attempts have been made to interpret the meaning of them. The reasons for this interest are not difficult to find. Dreams are odd and striking phenomena, similar to waking thought in some ways, but quite dissimilar in others. The objects which enter into the dream are usually everyday kinds of objects; similarly, the place where the dream occurs is usually a familiar one. Yet what happens in the dream is often quite unlike the happenings of everyday life. People may change into each other or into animals; the dreamer may be wafted through the centuries or across the oceans in no time at all, and the most frightful and wonderful events may happen to him.

In addition, dreams often have a very strong emotional content. This is obvious enough in the case of the nightmare, but even in the case of more ordinary dreams, strong emotions, both pleasant and more usually unpleasant, may be called forth.

Factual information is quite scant. When large numbers of dreams of people are examined, the settings in which the dreams occur, the characters appearing in them, the actions through which they go, and the emotions which they betray. Most dreams have some fairly definite setting, where the dreamer is in a conveyance such as an automobile, a train, an airplane, a boat or is walking along a street or road. Few dreams are set in recreational surroundings: amusement parks, at dances and parties, on the beach, watching sports events, and so on. More frequent than any of these settings, however, is the house or rooms in a house; Apparently the living-room is – the most popular, followed in turn by bedroom, kitchen, stairway, basement, bathroom, dining-room, and hall. Another are set in rural and out-of-doors surroundings. Men’s dreams tend to occur more frequently in out-of-door surroundings, women’s more frequently indoors. The remainindreams are difficult to classify with respect to their settings.

By taking into account the setting, Psychoanalysts often try to interpret certain aspects of the dream. The dream occurs in a conveyance, for instance, is interpreted in terms of the fact that the dreamer is going somewhere, is on the move; movement represents ideas such as ambition, fleeing from something, progress and achievement, breaking family ties, and so forth. Trains, automobiles, and other vehicles are instruments of power, and are thus interpreted as symbols for the vital energy of one’s instinctual impulses, particularly those of sex.

Recreational settings are usually sensual in character, being concerned with pleasure and fun, and imply an orientation towards pleasure rather than work.

A symbolic interpretation of this kind may be even more highly specialized; thus a basement is supposed to be a place where base deeds are committed, or it may represent base unconscious impulses. We shall be concerned with the validity of such interpretations later on; here let us merely note the fact that interpretations of this type are made by some people.

All kinds of emotions are attached to the actions and persons making up the dream, as well as to the settings. Quite generally unpleasant dreams are more numerous than pleasant ones, and apparently as one gets older the proportion of unpleasant dreams increases. The unpleasant emotions of fear, anger, and sadness are reported twice as frequently as the pleasant emotions of joy and happiness. Emotion in dreams is often taken to be an important aid in interpreting the dream. In this it differs very much from color; about one dream in three is colored, but the attempt to find any kind of interpretation whatsoever for the difference between colored and black-and-white dreams has proved very disappointing.

In addition to a setting, the dream must also have a cast. Sometime in dreams no one appears but the Dreamer himself. Sometimes two characters appear. Most of these additional characters are members of the dreamer’s family, friends, and acquaintances. Sometimes the characters in our dreams are strangers; they are supposed to represent the unknown, the ambiguous, and the uncertain ; sometimes they are interpreted as alien parts of our own personality which we may be reluctant to acknowledge as belonging to us. Prominent people are seldom found in dreams ; this may be because our dreams are concerned with matters that are emotionally relevant to us.

As far as actions in dreams are concerned, in dreams some cases are engaged in some kind of movement, such as walking, driving, running, falling, or climbing. Mostly these changes in location occur in his home environment. In another, passive activities such as standing, watching, looking, and talking are indulged in. There appears to be an absence of strenuous or routine activities in dreams – there is little in the way of working, buying or selling, typing, sewing, washing the dishes, and so forth. When energy is being expended in the dream it is in the service of pleasure, not in the routine duties of life. Women, generally speaking, have far fewer active dreams than men.

For majority of dreams such explanations are clearly insufficient, and we encounter two great groups of theories which attempt to interpret and explain dreams.

According to the first of these theories, dreams are prophetic in nature ; they warn us of dangers to be encountered in the future, they tell us what will happen if we do this or -that; they are looked upon as guide-posts which we may heed or neglect as we wish. This is probably the most common view of dreams which has been held by mankind.

If we take this hypothesis at all seriously, then a study of the art of dream interpretation clearly becomes of the greatest possible importance. The pattern was set by an Italian scholar called Artemi- dorus, who lived in the second century of the Christian era. His book was called Oneirocritics, which means The Art of Interpreting. Essentially, books of this nature are based on the view that the dream is a kind of secret language which requires a sort of dictionary before it can be understood. This dictionary is provided by the writer of the dream book in the form of an alphabetical list of things which might appear in the dream, each of which is followed by an explanation of its meaning. Thus, if the dreamer dreams about going on a journey, he looks up ‘Journey’ in his dream book and finds that it means death. This may of course be rather disturbing to him, but he may console him- self by the consideration that it need not necessarily be his own death which is being foretold in this fashion.

Few people would take this kind of dream interpretation very seriously; it is obviously analogous to astrology, and palmistry, in its unverified claims and its generally unlikely theoretical basis. Nevertheless, some scientists have taken the possibility of precognition seriously, One of the best known of these is J.W.Dunne, whose book An Experiment with Time was widely read in the twenties and thirties of 19th century.

We must turn to the quite different type of dream interpretation which is current. This is the theory propounded by Sigmund Freud. According to the Freudian theory dreams do not reveal anything about the future. Instead, they tell us something about our present un resolved and unconscious complexes and may lead us back to the early years of our lives.

There are three main hypotheses in this general theory. The first hypothesis is that the dream is not a meaningless jumble of images and ideas, accidentally thrown together, but rather that the dream as a whole, and every element in it, are meaningful.

The second point that Freud makes is that dreams are always in some sense a wish fulfillment; in other words, they have a purpose, and this purpose is the satisfaction of some desire or drive, usually of an unconscious character.

Thirdly, Freud believes that these desires and wishes, having been repressed from consciousness because they are unacceptable to the socialized mind of the dreamer, are not allowed to emerge even into the dream without disguise. A censor or super-ego watches over them and ensures that they can only emerge into the dream in a disguise so heavy that they are unrecognizable.

The idea that the dream is meaningful is, follows directly from the deterministic standpoint: i.e. from the view that all mental and physical events have causes and could be predicted if these causes were fully known.

Freud’s argument of the meaningfulness of dreams is directly connected with his general theory that all our acts are meaningfully determined; a theory which embraces mispronunciations, gestures, lapses, emotions, and so forth.

The second part of Freud’s doctrine, view that the dream is always a wish fulfillment. – This is linked up with his general theory of personality.

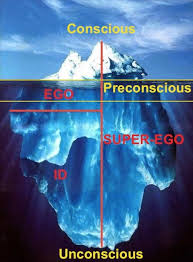

Roughly speaking, Freud recognized three main parts of personality : one, which he calls the id, is a kind of reservoir of unconscious drives and impulses, largely of a sexual nature; this reservoir, as it were, provides the dynamic energy for most of our activities. Opposed to it we have the so-called super-ego, which is partly conscious and partly un- conscious and which is the repository of social morality. Intervening between the two, and trying to resolve their opposition, is the ego(like the servant in between the two masters) i.e. the conscious part of our personality.

Connecting the Freud’s theory of personality and his theory of dream interpretation is quite simple: the forces of the id are constantly trying to gain control of the ego and to force themselves into consciousness. During the individual’s waking life, the super-ego strongly represses them and keeps them unconscious; during sleep, however, the super-ego is less watchful, and consequently some of the desires start up in the id and are allowed to escape in the form of dreams. However, the super-ego may nod, but it is not quite asleep, and consequently these wish-fulfilling thoughts require to be heavily disguised. This disguise is stage- managed by what Freud calls the DreamWorks. Accordingly, it is necessary to distinguish between the manifest dream, i.e. the dream as experienced and perhaps written down, and the latent dream, i.e. the thoughts, wishes, and desires ex- pressed in the dream with their disguises removed.

For the task of the analyst and interpreter on this view is to explain the manifest dream in terms of the latent dream, Freud uses two methods. The first is the method of symbolic interpretation. The other method, – of much greater general interest and importance, is the method of association.

Freud uses the theory of Symbolism, very much like the old dream books, Freud provides whole lists of symbols standing for certain things and certain actions. Freud concentrates almost exclusively on sex and sexual relations. The male sex organ is represented in the dream by a bewildering variety of symbols. Anything that is long and pointed – a stick, a cigar, a chimney, a steeple, the stem of a flower – is so interpreted because of the obvious physical resemblance. A pistol, a knife, forceps, a gun – these may stand for the penis because they eject and penetrate; similarly a plough may become a sex symbol because it penetrates the earth. Riding a horse, climbing stairs, and many, many other common-sense activities stand for intercourse. Hollow objects and containers are feminine symbols: houses, boxes, saucepans, vases – all these represent the vagina. Members of the family are frequently said to be symbolically represented in the dream; thus the father and mother may in the dream appear as king and queen.

A more reasonable alternative theory is based on the method of free association. The technique of free association is based on the belief that ideas became linked through similarity or through contiguity and that mental life could be understood entirely in terms of such associations. If ideas are linked in a causal manner, as is suggested by this theory, then we should be able to find links between manifest and latent phenomena by starting out with the former and, through a chain of associations, penetrate to the latter. In other words, what is suggested is this : starting out with certain unacceptable ideas which seek expression, we emerge finally with unintelligible ideas contained in the manifest dream. These, having been produced by the original latent ideas, are linked to them by a chain of associations, and we shall be able to re-discover the original ideas by going back over this chain of ideas. In order to do this, Freud starts out by taking a single idea from the manifest dream and asking the subject to fix that idea in his mind and say aloud any- thing that comes into his mind associated with that original idea. The hope is that in due course a chain of associations will lead to the latent causal idea.

Nevertheless, the idea of using the method of association in exploring the contents of the mind is a highly original and brilliant one, and much credit must go to the man who first introduced it into psychology. This man, contrary to popular belief, was not Freud, however, but Sir Francis Galton. Galton’s name is probably best known through his initiation of the Eugenics movement, but his claims to fame extend in many different directions. He has many claims to be called the founder of modern psychology Galton tried out on himself an elaborate system of word association tests and reached conclusions very similar to those later popularized by Freud and Jung.

Making use, then, of these methods of symbolic interpretations and of association, both discovered long before his time, Freud proceeded to analyse the nature of the dream. He discusses his discoveries in terms of so-called- mechanisms which are active in the dream. The first of these mechanisms he calls that of dramatization. This simply de- notes the fact, already familiar to most people, that the major part in dreams is played by visual images, and that conceptual thought appears to be resolved into some form of plastic representation. Freud likens this to the pictorial manner in which cartoons portray conceptual problems. The cartoonist is faced with the same difficulty as the dreamer. He cannot express concepts in words, but has to give them some form of dramatic and pictorial representation. In addition to visual images, verbal ones also may appear, and here the material meaning of words may often be associated with a rather uncommon meaning.

Closely related to the mechanism of dramatization is that of symbolism, which we have already discussed. Here is an example which will illustrate the general mechanism of dramatization and also that of symbolism in dreams. In this dream a young woman dreamed that a man was trying to mount a very frisky small brown horse. He made three un- successful attempts; at the fourth he managed to take his seat in the saddle and rode off. Horse-riding, as was mentioned earlier, often represents coitus in Freud’s general theory of symbolism. What happens when we look at the subject’s associations? The horse reminded the dreamer that in her childhood she had been given the French word ‘ chevaV as a nickname; in addition, this woman was a small and very lively brunette, like the horse in the dream. The man who was trying to mount the horse was one of the dreamer’s most intimate friends. In flirting with him she had gone to such lengths that three times he had wished to take advantage of her but each time her moral sentiments had got the upper hand at the last moment. Inhibitions are not so strong in the dream, and the fourth attempt therefore ended in a wish fulfillment.

Another mechanism acting in the dream work is said to be that of condensation. The manifest content is only an abbreviation of the latent content. As Freud puts it ‘The dream is meager, paltry, and laconic in comparison with the range and copiousness of the dream thoughts.’ The images of the manifest content are said by Freud to be over-determined: i.e. each manifest element depends on several latent causes and consequently expresses several hidden thoughts.

The last dream mechanism is that of displacement. It is a process whereby the emotional content is detached from its proper object and attached instead to an unimportant or subsidiary one; the essential feature of the latent content of the dream accordingly may sometimes be hardly represented at all in the manifest content, at least to outward appearances; it has been displaced under some apparently innocuous object.

Now, it will be remembered that the central piece of Freud’s whole theory, the one bit that is original and not derivative, is the notion that symbols and other dream mechanisms are used to hide something so obnoxious, so contrary to the morality of the patient, that he cannot bear to consider it undisguised, even in his dream. This notion seems so contrary to the most obvious facts that it is difficult to see how it can ever have been seriously entertained.

Let us list some of these objections. In the first place, the notion which is expressed symbolically in one dream may be quite blatantly and directly expressed in another. We have a highly symbolic and involved dream which is interpreted as meaning that we want to kill a relative or have intercourse with someone, only to find that in another dream these ideas are expressed perfectly clearly in the sense that we do actually kill our relative or have intercourse with this girl. What is the point of putting on the masquerade on one occasion, only to discard it on another?

A second objection is that the symbols which are supposed to hide the dream-thought very frequently do nothing of the kind. Many people who have no knowledge of psycho-analysis are able to interpret the sexual symbols which occur in dreams without any difficulty at all. After all, let us face the fact that there are many slang expressions in use referring to sexual activities and sexual anatomy, and that these slang terms are only too often identical with Freudian symbols. There seems to be little disguise in a person’s dreaming about a cock, symbolizing the penis, when the very same person would not even know the term penis and always refers to his sex organ as his ‘cock’. Freud seems to have been singularly remote from the realities of everyday life.

A last point of criticism has been raised by Calvin S.Hall, He asks why there are so many symbols for the same referent. In his search of the literature he found 102 different dream- symbols for the penis, ninety-five for the vagina, and fifty five for sexual intercourse. Why, he asks, is it necessary to hide these reprehensible referents behind such a vast array of masks?

Let us see to what extent Freud’s theory is in fact supported by the dream we have quoted. First of all let us take the young lady nicknamed ‘ ChevaP, who at the last moment frustrated three determined efforts at seduction by her boy friend, only to have the success of the enterprise presented to her in a dream in symbolic form. According to the Freudian theory, we would have to believe that the notion of actually having intercourse with her boy friend was so shocking to this young lady, and so much outraged her moral instincts and training, that she could not even contemplate the idea in her sleep, thus having to disguise it in symbols. This, surely, is a very unconvincing argument; to imagine that a young girl, who would several times running indulge in such heated love-making that she was on the point of losing her virginity, could not bear to contemplate the possibility of having intercourse, and had to repress it into her unconscious, could surely not be seriously maintained, even by a psychoanalyst following obediently in the steps of the master.

Is it possible to substitute a more plausible theory.An interesting move in this direction has recently been made by C.S.Hall, a well- known American psychologist. His argument is as follows. The same objective fact – say sexual intercourse may have widely different meanings to different people. One conception might be that of a generative or reproductive activity; another one might be that of an aggressive physical attack. It is these different conceptions of one and the same objective fact which are expressed in the special choice of symbolism of the dream. Dreaming of the ploughing of a field or the planting of seeds is a symbolic representation of the sex act as being generative or reproductive. Dreaming of shooting a person with a gun, stabbing someone with a dagger, or running down with an automobile, symbolizes the view of the sex act as an aggressive attack. According to this theory, symbols in dreams are not used to hide the meaning of the dream, but quite on the contrary, are used to reveal not only the act of the person with whom the dreamer is concerned, but also his conceptions of these actions or persons.

If a person dreams of his mother, and if his mother in the dream is symbolized by a cow or a queen, Freud would interpret this to mean that the dreamer is disguising his mother in this fashion because he cannot bear to reveal, even to him- self, the wishes and ideas expressed in the dream and connected with the mother figure. In terms of Hall’s theory, the interpretation would be that the dreamer not only wishes to represent his mother, but also wants to indicate that he regards her as a nutrient kind of person (cow), or a regal and remote kind of person (queen). The use of symbols, then, is an expressive device, not a means of disguise, and it is note-worthy that in waking life, symbols are used for precisely the same reason: a lion stands for courage, a snake for evil, and an owl for wisdom. Symbols such as these convey in terse and concise language abstruse and complex conceptions.

Certain symbols, on this theory, are chosen more frequently than others because they represent in a single object a variety of conceptions. The moon, for instance, is such a condensed and over-determined symbol of woman; the monthly phases of the moon resemble the menstrual cycle ; the filling out of the moon from new to full symbolizes the rounding out of the woman during pregnancy. The moon is inferior to the sun; the moon is changeable like a fickle woman, while the sun is constant. The moon controls the ebb and flow of the tides, again linking it to the family rhythm. The moon, shedding her weak light, embodies the idea of feminine frailty. Hall concludes : ‘Rhythm, change, fruitfulness, weakness, submissiveness, all of the conventional conceptions of woman, are compressed into a single visible object.’

This suggests that all theories of dream interpretation may have a certain limited amount of truth in them, but that they do not possess universal significance, and apply only to a relatively small part of the field. This conclusion is strengthened when it is further realized that quite probably the person whose dreams are being analysed begins to learn the hypothetical symbolic language of the analyst and obediently makes use of it in his dreams. This may account for the fact that Freudian analysts always report that their patients dream in Freudian symbols, whereas analysts who follow the teaching of Jung report that their patients always dream in Jungian symbols, which are entirely different from the Freudian symbols.

There is one further difficulty in accepting the symbolic interpretations presented by so many dream interpreters. How, it may be asked, do we know that a motor-car stands for the sexual drive; might it not simply stand for a motor-car? In other words, how can the poor dreamer ever dream about anything whatsoever, such as a house, a screw, a syringe, a railway engine, a gun, the moon, a horse, walking, riding, climbing stairs, or indeed anything under the sun, if these things are immediately taken to symbolize something else? What would happen if you took a very commonplace, everyday event such as a train journey and regarded it as an account of a dream? The reader will see in the following paragraph how such a very simple and straightforward description is absolutely riddled with Freudian symbols of one kind or another. Relevant words and phrases have been italicized to make identification easier.

To begin with, we pack our trunks, carry them downstairs, and call a taxi. We put our trunks inside, then enter ourselves. The taxi surges forward, but the traffic soon brings us to a halt and the driver rhythmically moves his hand up and down to indicate that he is stopping. Finally we drive into the station. There is still time left and we decide to write a postcard. We sharpen a pencil, but the point drops off and we test our fountain pen by splashing some drops of ink on to the blotting-paper. We push the postcard through the slot of the pillar-box and then pass the barrier and enter the train. The powerful engine blows off steam and finally starts. Very soon, however, the train enters a dark tunnel. The rhythmic sounds of the wheels going over the intersections send us to sleep, but we rouse ourselves and go to the dining-car, where the waiter pours coffee into a cup from a long- nosed coffee-pot. The train is going very fast now and we bob up and down in our seats. The semaphore arms on the signal masts rise as we approach and fall again as we pass. We look out of the window and see cows in the pasture, horses chasing each other, and farmers ploughing the ground and sowing seeds. The sun is setting now and the moon is rising. Finally the train pulls into the station and we have arrived.

It will be clear that there is practically nothing that we can do or say on our journey which is not a flagrant sex symbol. If, therefore, we wanted to dream of a railway journey, the thing would just be impossible. All we can ever dream about, if we follow the Freudian theory, is sex, sex, and sex again.

The critical thinker may feel at this point that while the discussion may have been quite interesting at times, it has not produced a single fact which could be regarded as having scientific validity. Everything is surmise, conjecture, and interpretation; judgements are made in terms of what seems reasonable and fitting. This is not the method of science, and that is precisely what is missing in all the work we have been summarizing so far.

There is always a necessity of having control groups in psychological investigations. No control group has ever been used in experimental studies of dream interpretation by psychoanalysts, yet the necessity for such a control would be obvious on reflection. According to Freud’s theory, the manifest dream leads back to the latent dreams in terms of symbolization and in terms of free association. This is used as an argument in favour of the view that the alleged latent dream has caused the manifest dream, but the control experiment is missing. What would happen if we took a dream reported by person A and got person B to associate to the various elements of that dream? Having performed this experiment a number of times, I have come to the conclusion that the associations very soon lead us back to precisely the same complexes which we would have reached if we had started out with one of person B’s own dreams. In other words, the starting point is quite irrelevant; so a person’s thoughts and associations tend to lead towards his personal troubles, desires, and wishes of the present moment.

Many other alternative theories could be formulated and would have to be tested before anything decisive could be said about the value of the Freudian hypothesis. In the absence of such work, our verdict must be that, such evidence as there is leads one to agree with the many judges who have said that what is new in the Freudian theory is not true, and what is true in it is not new.

Actually it would not be quite correct to say that no experimental work on dreams had been done. There are a number of promising leads, but, as might have been expected, these have come from the ranks of academic psychologists and not from psychoanalysts themselves. Of particular interest is the work of Luria, a Russian psychologist who attacked the problem of dream interpretation as part of a wider problem, namely the experimental investigation of complexes. His technique consisted in implanting complexes under hypnosis and observing the various reactions, including dreams, of the subjects after they had recovered from the hypnotic trance. The implanted complexes were of course unconscious in the sense that the subject knew nothing about them on being interrogated, and had no notion of anything that had transpired during the hypnotic trance.

An example may make clearer just what the procedure is. It is taken from a study of H. J. Eysenck carried out to check some of the findings reported by Luria. The subject, a thirty-two-year-old woman, is hypnotized and the following situation is power- fully impressed upon her as having actually happened. She is walking across Hampstead Heath late at night when suddenly she hears footsteps behind her; she turns and sees a man running after her; she tries to escape but is caught, flung to the ground, and raped. On waking from the hypnosis, she is rather perturbed, trembles a little, but cannot explain the cause of her uneasiness ; she has completely forgotten the event suggested to her under hypnosis. She is then asked to lie down and rest; after a few minutes she falls into a natural sleep, but is immediately woken up and asked to recall anything she might have been dreaming of. She re- counts that in her dream she was in some desolate spot which she cannot locate and that suddenly a big Negro, brandishing a knife, was attacking her; he managed to prick her thigh with it. The symbolic re-interpretation of the hypnotic trance in the dream is clear enough and tends to substantiate the fact that dreams express in dramatized and symbolic form certain thoughts which in the waking state would probably be conceptualized in a more direct form.

This method of investigation has considerable promise, but unfortunately very little has been done with it. Realizing, then, that nothing certain is known, can we at least propound a general theory which summarizes what we have said and is not contradicted by any of the known facts? Such a theory might run as follows : The mind tends to be constantly active. In the waking state most of the material for this activity is provided by perceptions of events in the outer world; only occasionally, as in problem-solving and day-dreaming, are there long stretches of internal activity withdrawn from external stimulation. During sleep such external stimulation is more or less completely absent, and consequently mental activity ceases to be governed by external stimulation and becomes purely internal.

In general this mental activity is very much concerned with the same problems that occupy waking thought. Our wishes, hopes, fears, our problems and their solutions, our relationships with other people – these are the things we think about in our waking life, and these are the things we dream about when we are asleep. The main difference is that mental activity in sleep appears to be at a lower level of complexity and to find expression in a more archaic mode of presentation. The generalizing and conceptualizing parts of the mind seem to be dormant, and their function is taken over by a more primitive method of pictorial representation. It is this primitivization of the thought processes which leads to the emergence of symbolism, which thus serves very much the function Hall has given it in his theory.

This symbolizing activity is, of course, determined to a large extent by previous learning. In general, symbols are relative to the education and experience of the dreamer, although certain symbols, such as the moon, are very widely used because they are familiar to almost all human beings.

Until evidence of a more rigorous kind than is available now is produced in favour of this hypothesis, we can only say that no confident answer can be given. If and when the proper experiments are performed, due care being given to the use of control groups and other essential safeguards. At the moment the only fit verdict seems to be the Scottish one of ‘not proven’.