Dr. V.K.Maheshwari, M.A(Socio, Phil) B.Sc. M. Ed, Ph.D

Former Principal, K.L.D.A.V.(P.G) College, Roorkee, India

Considered historically, the present caste system is a remnant of medieval times, in ancient India, caste was by no means so rigid or exclusive. In Buddhistic and post Buddhistic periods the castes and sub-castes multiplied and gradually became more rigid. Originally there were only four castes. Then developed a large number of occupational castes corresponding to the medieval trade guilds –institutions which have given the central idea for the school of modern thinkers known as Guild Socialists, whose leaders, like Mr. Penty, want to bring back the social organization of the ‘merrie England’ days and call it ‘post-industrialism.’ “Merrie England” , refers to an English auto stereotype , a utopion conception of English society and culture based on an idyllic pastoral way of life that was allegedly prevalent at some time between the Middle Ages and the onset of the Industrial Revolution.( More broadly, it connotes a putative essential Englishness with nostalgic overtones, incorporating such cultural symbols as the thatched cottage, the , country inn the cup of tea and the Sunday roast. Children’s storybooks and fairytales written in the Victorian period often used this as a setting as it is seen as a mythical utopia. They often contain nature-loving mythological creatures such as elves and fairies, as well as Robin Hood. It may be treated both as a product of the sentimental nostalgic imagination and as an ideological or political construct, often underwriting various sorts of conservative world-views. )

Strange as it may seem, the system of varna was the outcome of tolerance and trust. Originally varnas were assigned to people based on their aptitude and qualitiesThe system of varna insisted that the law of social life should not be cold and cruel competition, but harmony and co-operation. Society should not be a field of rivalry among individuals. Actually the varnas were designated to a person based on one’s aptitude, quality, mental state and characteristic. Although birth or parentage may have played an important role in the later times, the original system seems to be based on the quality of a person rather than on birth alone. Even when the varna was ascribed based on birth, there are a number of examples from the mythology and history of ancient India to demonstrate the flexibility and mobility among the varnas.

Though it may now have degenerated into an instrument of oppression and intolerance and tends to perpetuate inequality and develop the spirit of exclusiveness, these unfortunate effects were not the central motives of the varna system. However, there are a number of exceptions in the entire period that shows the flexibility of the system.

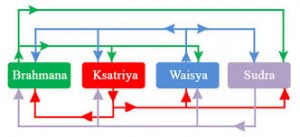

There were four varnas: brahmin, ksatriya, vaisya and sudra. The basic idea was division of labor in the society. Brahmin were the people who preached spiritual teachings to the society and lived spiritual lives . Ksatriya were the people who protected the society against external attacks and maintained internal order .Businessmen, traders and farmers came under this category of Vaisya . Sudras were the people engaged in services. Carpenters, blacksmiths, goldsmiths, cobblers, porters etc., fell under this category. This system ensured that the religious, political, financial and physical powers were all separated into four different social classes. Due to this fair separation of political and intellectual powers, ancient Indian society could not turn itself into a theocratic or autocratic society.

In the beginning, there was only one varna in the ancient Indian society. “We were all brahmins or all sudras,” says Brhadaranyaka Upanisad (1.4, 11-5, 1.31) and also Mahabharata (12.188). A smrti text says that one is born a sudra, and through purification he becomes a brahmin. According to Bhagavada Gita, varna is conferred on the basis of the intrinsic nature of an individual, which is a combination of three gunas (qualities): sattva, rajas, and tamas. In the Mahabharata SantiParva, Yudhisthira defines a brahmin as one who is truthful, forgiving, and kind. He clearly points out that a brahmin is not a brahmin just because he is born in a brahmin family, nor is a sudra a sudra because his parents are sudras. The same concept is mentioned in Manu Smrti. Another scripture Apastamba Dharmasutra states that by birth every human being is a sudra. It is by education and upbringing that one becomes ‘twice born’, that is, a dvija.

Bhagavada Gita also says, “Of brahmins, ksatriyas and vaisyas, as also the sudras, O Arjuna, and the duties are distributed according to the qualities born of their own nature.”

According to Rig Veda (IX.112.3), the poet refers to his diverse parentage: “I am a reciter of hymns, my father is a physician and my mother grinds corn with stones. We desire to obtain wealth in various actions.”

Actually the varnas were designated to a person based on one’s aptitude, quality, mental state and characteristic. Although birth or parentage may have played an important role in the later times, the original system seems to be based on the quality of a person rather than on birth alone. Even when the varna was ascribed based on birth, there are a number of examples from the mythology and history of ancient India to demonstrate the flexibility and mobility among the varnas.

Vyäsa, a brahmin sage and the most revered author of many Vedic scriptures including the Vedas, Mahabharata, was the son of Satyavati, a sudra woman. Vyäsa’s father, Päräsara, was also a son of a candala woman and yet was considered a brahmin based on his Vedic wisdom. Another popular Vedic sage, Välmiki was initially a hunter. Sage Aitareya, author of Aitareya Upanisad, was born of a sudra woman. Vasishtha, son of a prostitute, was established as a brahmin. In Chandogya Upanisad, the honesty of Satyakäma establishes his brahminhood, even though he is the son of a maidservant. Visvamitra, born in a ksatriya family becomes a sage. The priest Vidathin Bhärdväja became a ksatriya as soon as he was adopted by King Bharata .Janaka, a ksatriya by birth, attained the rank of a brahmin by virtue of his ripe wisdom and saintly character and is considered a rajarishi (king-sage). Vidura, a brahmin visionary, was born to a woman servant of the palace. The Kauravas and Pandavas were the descendants of Satyavati, a fisher-woman, and Vyäsa, a brahmin. In spite of this mixed heredity, the Kauravas and Pandavas were known as ksatriyas on the basis of their occupation. In the later Vedic times, Chandragupta Maurya, originally from the Muria tribe, goes on to become the famous Mauryan emperor of Magadha. Similarly, his descendant, King Asoka, was the son of a maidservant. The Sanskrit poet and author, Kalidasa is also not known to be a brahmin by birth. His works are considered among the most important Sanskrit works. In the medieval period, saint Thiruvalluvar, author of ‘Thirukural’ was a weaver. Other saints such as Kabir, Sura Dasa, Ram Dasa and Tukaram came from the sudra class also.

Scholars differ as to what exact part each of the various factors—race, occupation, etc. played in the evolution of Indian castes. According to Sir Denzil Ibbetson.( Punjab Castes (reprinted from Ibbetson’s Report), Government Press, Lahore, 1916, pp. 9 et. seq. ) the various factors were tribal divisions common to all primitive societies; the guilds based upon hereditary occupation ‘common to the middle life of all communities ;’ the exaltation of the priestly office and of the Levitical blood, and the ‘ preservation and support of this principle by the elaboration from the theories of the Hindu creed or cosmogony of a purely artificial set of rules regulating marriage and intermarriage, declaring certain occupations and foods to be impure and polluting, and prescribing the conditions and degree of social intercourse permitted between the several castes,’ “Add to these,” says Ibbetson, “the pride of social rank and the pride of blood which are natural to man, and which alone could reconcile a nation to restrictions at once irksome from a domestic, and burdensome from a material point of view; and it is hardly to be wondered at that caste should have assumed the rigidity which distinguishes it in India.”

Mr. Nesfield, however, considers that the classification into castes is based solely on occupation. “Function and function only,” says he, “was the foundation upon which the whole caste system of India was built up.”( Nesfield, A Brief View of the Caste System in North-Westren Province and Oudh.) (Quoted in The People of India by Sir Herbert Risley, 2nd edition, Calcutta, 1915, pp. 265 et. seq.) to him ‘each caste or group of castes represents one or other of those progressive stages of culture which have marked the industrial development of mankind not only in India, but in every other country in the world wherein some advance has been made from primeval savagery to the arts and industries of civilized life. The rank of any caste as high or low depends upon whether the industry, represented by the caste belongs to an advanced or backward stage of culture.’

Historian. M. Senart,( Les Cstes d’ans l’Inde. (Quoted by Risley, op. cit., pp. 267 et. seq.) the French Indologist, sees in Hindu caste only a parallel of the Roman and Greek systems. Risley represents M. Senart as maintaining that caste is the ‘normal development of ancient Aryan institutions, which assumed this form in the struggle to adapt themselves to the conditions with which they came into contact in India.’ M. Senart relies greatly upon the general parallelism that may be traced between the social organization of the Hindus and that of the earlier Greeks and Romans. He points out a close correspondence between the three series of groups, gens, curia tribe at Rome; family , phratria, phuli in Greece: and family, gotra, caste in India.’ He seeks to show ‘ from the records of classical antiquity that the leading principles which underlie the caste system form part of a stock of usage and tradition coomon to all branches of the Aryan people.’ Regulation of marriage by caste was by no means peculiar to India, for, as Mr. Senart points out, the Athenian genos and the Roman gens present striking resemblances to the Inidan gotra. ‘We learn from Plutarch that the Romans never married a woman of their own kin, and among the matrons who figure in classical literature none bears the same gentile name as her husband. Nor was endogamy unkown. In Athens in the time of ( Les Cstes d’ans l’Inde. (Quoted by Risley, op. cit., pp. 267 et. seq.) Demosthenes membership of a phratria was confined to the offspring of the families belonging to the group. In Rome, the long struggle of the plebeians to obtain the Jus connubii with patrician women belongs to the same class of facts; and the patricians, according to M. Senart, were guarding the endogamous rights of their order—or should we not rather say the hypergamous rights?—for in Rome, as in Athens, the primary duty of marrying a woman of equal rank did not exclude the possibility of union with women of humbler origin, foreigners or liberated slaves. Their children, like those of a Shudra in the Indian system, were condemned to a lower status by reason of the gulf of religion that separated their parents. We read in Manu how the gods disdain the oblations offered by a Shudra: in Rome they were equally offended by the presence of a stranger at the sacrifice of the gens.’ ‘The Roman confarreatio has its parallel in the got kanala or “tribal trencher” of the Punjab, the connubial meal, by partaking of which the wife is transferred from her own exogamous group to that of her husband.’

M. Senart traces the parallel in notions about food also. ‘In Rome as in India, daily libations were offered to ancestors, and the funeral feasts of the Greeks and Romans … correspond to the Shraddha of Hindu usage, which… is an ideal prolongation of the family meal.’ M. Senart seems even to find in the communal meals of the Persians and in the Roman charistia , from which were excluded not only strangers but any members of the family whose conduct had been unworthy.

The analogue of the communal feast at which a social offender in India is received back to caste.’ Regarding outcasting and the powers of the caste panchayat M. Senart points out:” The exclusion from religious and social intercourse symbolized by the Roman interdict aqua et igni corresponds to the ancient Indian ritual for expulsion from caste, where a slave fills the offender’s vessel with water and solemnly pours it out on the ground, and to the familiar formula hukka pani band karna, in which the modern luxury of tobacco takes the place of the sacred fire of the Roman excommunication. Even the caste panchayat that wields these formidable sanctions has its parallel in the family councils which in Greece, Rome and ancient Germany assisted at the exercise of the patria potestas and in the chief of the gens, who, like the matabar of a caste, decided disputes between its members and gave decisions which were recognized by the State.”

Risley quotes Sir S. Dill ( Roman Society in the Last Century of the Western Empire, 1899. See Risley, op. cit., pp.271 et. seq. ) as pointing out ‘how an almost Oriental system of caste had made all public functions in Rome hereditary, ‘from the senator to the waterman on the Tiber or the sentinel at a frontier post’. ‘The Navicularii who maintained vessels for transport by sea, The Pistores who provided bread for the people of Italy, the Pecuarii and Suarii who kept up the supply of butcher’s meat were all organized on a system as rigid and tyrannical as that which Prevails in India… Each caste was bound down to its characteristic occupation, and its matrimonial arrangements were governed by the curious rule that a man must marry within the caste, while if a woman married outside of it, her husband acquired her status and had to take on the public duties that went with it., The rigidity of caste in Rome can be imagined from the account that follows:( Sir S. Dill, quoted by Risley.)

“The man who brought the grain of Africa to the public stores at Ostia, the baker who made it into loaves for distribution, the butchers who brought pig from Samnium, Lucania or Bruttium, the purveyors of wine and oil, the men who fed the furnaces of the public baths, were bound to their callings from one generation to another. It was the principle of rural serfdom applied to social functions. Every avenue of escape was closed. A man was bound to his calling not only by his father’s but by his mother’s condition. Men were not permitted to marry out of their guild. If the daughter of one of the baker caste married a man not belonging to it, her husband was bound to her father’s calling. Not even a dispensation obtained by some means from the imperial chancery, not even the power of the Church. Could avail to break the chain of servitude.”

Even to-day where is the country in which caste does not play a prominent part? The European critics forget the beam in their own eye to a new order for the new conditions. If a Vedic Indian happened to visit India any day in the post-Buddhistic period he would feel bewildered at the new and complicated system of caste prevailing in society. And there can be no doubt that a politically free India will lose no time in effecting fresh adjustments. As it is, caste has ceased to do us any good at all, and its evils have in certain respects become accentuated.

It is said the Hindus are caste-redden, and therefore unfit for democracy. It is forgotten that the Hindus in the past had at least as much of democracy as the Romans and the Athenicans. The West used to talk like that also of Japan. Not very long ago, that gifted writer, Lafcadio Hearn wrote: ( Japan: An interpretation (Macmillan), p. 260. )

“ There was a division also into castes—Kabane or Sei. ( Dr. Florenz, a leading authority on ancient Japanese civilization, who gives the meaning of Sei as equivalent to that of the Sanskrit varna, signifying ‘caste’ or ‘colour.’) Every family in the three great divisions of Japanese society belonged to some caste; and each caste represented at first some occupation or calling.” Large classes of persons existed in Japan, who were literally known as ‘less than men.’ Says Mr. Hearn:

“Outside of the three classes of commoners, and hopelessly below the lowest of them, large classes of persons existed who were not reckoned as Japanese, and scarcely accounted human beings. Officially they were mentioned generically as chori, and were counted with the peculiar numerals used in counting animals: immiki, nihiki, sambiki, etc. Even to-day they are commonly referred to not as persons (hito) but as ‘things’ (mono)… to English readers (chiefly) through Mr. Mitford’s yet unrivalled Tales of Old Japan) they are known as Eta; but their appellations varied according to their callings. They were pariah people.” The Eta, we are told, “lived always in the suburbs or immediate neighbourhood of towns, but only in separate settlements of their own. They could enter the town to sell their wares or to make purchases; but they could not enter any shop, except the shop of a dealer in footgear. As professional singers they were tolerated; but they were forbidden to enter any house—so they could perform their music or sing their songs only in the street or in a garden. Any occupation other than their hereditary callings was strictly forbidden to them. Between the lowest of the commercial classes and the Eta, the barrier was impassable as any created by caste tradition in India; and never was ghetto more separated from the rest of a European city by walls and gates, than an Eta settlement from the rest of Japanese town by social prejudice. No Japanese would dream of entering an Eta settlement unless obliged to so in some official capacity.”

The Eta, and then the ‘pariahs,’ called Hinin—a name signifying ‘not-human-beings’ ‘Under this appellation were included professional mendicants, wandering ministrels, actors, certain classes of prostitutes and persons out lawed by society. The Hinin had their own chiefs and their own laws. Any person expelled from a Japanese community might join the Hinin; but the signified good-bye to the rest of humanity.’

Were the caste-ridden Japanese fit for ‘progress’ and democracy? Says hearn:

“Those who write to-day about the extraordinary capacity of the Japanese for organization and about the ‘democratic spirit’ of the people as natural proof of their fitness for representative government in the Western sense mistake appearances for realities. The truth is that the extraordinary capacity of the Japanese for communal organization is the strongest possible evidence of their unfitness for any modern democratic form of government. Superficially the difference between Japanese social organization and local self-government in the modern American or the English colonial meaning of the terms appears slight; and we may justify admire the perfect self-discipline of a Japanese community. But the real difference between the two is fundamental, prodigious, measurable only by thousands of years.”

Hearn’s gloomy prophecies notwithstanding, all these caste and class distinctions have now practically disappeared in Japan because the Government co-operated with the people in the matter and used all its influence towards the abolition of the distinctions and divisions. Japan has been able to overthrow this system because of her political and economic independence. If India had been free she would have done the same.

In India the reformers are working against heavy odds, for they have to contend against prejudice and ignorance without absolutely any help from the state. In fact, the alien bureaucracy has devised new methods of perpetuating the old system and making it sub serve their own ends. Recruitment for the army is confined to castes called the ‘military castes.’ It is not every man who can pass the fitness tests that will be accepted by the recruiting officer. He must come from one of the ‘military castes.’ Who are expected to be more ignorant and ‘loyal’ than the other castes. Then the right to buy land is also regulated by caste. In the Punjab they have a list of castes for the Land Alienation Act, which are supposed to be ‘agricultural castes.’ People who have not been actual cultivators for several generations, whose chief vocation now is commerce or industry or state service are privileged under this Act because of their caste label. Such absurdities derive their sanction not from the Indian caste system but from the imperialist policy of playing off’ military and agricultural’ against’ non-military and non-agricultural castes’ and of trying to create a caste of ‘loyalists.’

Those who think that the British Government and the Christian missionary will rid India of the evils of caste, build castles in the air. The bureaucracy only want to give caste a new orientation to make it subseve who thinks that ‘Christianity’ has ‘emancipated’ the lower caste people, whereas Christianity in India is even more superficial than these observers. The foreign missionary, who depends on patronage from his own country, is anxious to show results in figures, and solid qualitative work is neglected.

Caste in India is by no means confined to the Hindu. So far as the industrial order of hereditary vocational guilds is concerned Islam did not affect it much. Caste plays an important part even in the life of the Mussalman though he has avoided its grossed forms like untouchability. Christianity has done not even that much, caste and untouchability have been affected but little among the converts.

Hope lies only in a politically free India in which the progressive elements will be as free to effect new adjustments as they were and are in Japan. Till that day comes we have to continue doing our best to overcome the impediments, but we know all the time that the results cannot be proportionate to our efforts