Dr. V.K.Maheshwari, M.A(Socio, Phil) B.Sc. M. Ed, Ph.D

Former Principal, K.L.D.A.V.(P.G) College, Roorkee, India

There has been so much recent talk of progress in the areas of curriculum innovation and textbook revision that few people outside the field of teaching understand how bad most of our elementary school materials still are.

Curriculum is concerned with making general statements about language learning, learning purpose, experience, evaluation, and the role and relationships of teachers and learners. Syllabuses, on the other hand, are more localized and are based on accounts and records of what actually happens at the classroom level as teachers and learners apply a given curriculum to their own situation.

Syllabus basically means a concise statement or table of the heads of a discourse, the contents of a treatise, the subjects of a series of lectures. In the form that many of us will have been familiar with it is connected with courses leading to examinations – teachers talk of the syllabus as, a series of headings with some additional notes which set out the areas that may be examined.

A syllabus will not generally indicate the relative importance of its topics or the order in which they are to be studied. In some cases those who compile a syllabus tend to follow the traditional textbook approach of an ‘order of contents’, or a pattern prescribed by a ‘logical’ approach to the subject, or – consciously or unconsciously – a the shape of a university course in which they may have participated. Thus, a curriculum which focuses on syllabus is only concerned with content. Curriculum is a body of knowledge-content and/or subjects. Education in this sense, is the process by which these are transmitted or ‘delivered’ to students by the most effective methods that can be devised .

Where people still equate curriculum with a syllabus they are likely to limit their planning to a consideration of the content or the body of knowledge that they wish to transmit. This view of curriculum has been adopted by many teachers in schools’, as issues of curriculum have no concern to them, since they have not regarded their task as being to transmit bodies of knowledge in this manner’.

The concept of curriculum is very wide and extensive. It includes all those experiences which a student gets in the aegis of the school. It includes all academic and co-curricular activities inside and outside the classroom. The curriculum can be understood in the form of activity and experience.

The term ‘syllabus’ is often used in the sense of the term ‘curriculum’. In fact, the subject matter for an intellectual subject is called content. When this content is organized in view of teaching in the classroom, this is called syllabus.

Thus, the syllabus presents the definite knowledge regarding the amount of knowledge to be given to students during the course of teaching of different subjects; while the curriculum is totality of educational activities, the teacher would complete .

Teaching can be made more effective if a teacher is fully satisfied with the curriculum which he has to teach. Also, he should know its utility. It can be possible only when he studies the prevalent syllabus critically. It should be fully clear to him that each subject has certain specific aims, which his students have to achieve. A teacher should examine these aims and how they can be achieved on the basis of the present syllabus.

From this view, the prevalent syllabus following are the bases for its critical appraisal :

Syllabus in Relation to Objectives : An objective is an goal or end point of something towards which actions are directed. Objectives generally indicate the end points of a journey. They specify where you want to be or what you intend to achieve at the end of a process. An educational objective is that achievement which a specific educational instruction is expected to make or accomplish. It is the outcome of any educational instruction. It is the purpose for which any particular educational undertaking is carried out.

Bloom’ Benjamin’s has put forward a taxonomy of educational objectives, which provides a practical framework within which educational objectives could be organized and measured. In this taxonomy Bloom divided educational objectives into three domains. These are;

Cognitive domain (intellectual capability, ie., knowledge, or ’think’)

The cognitive domain involves those objectives that deal with the development of intellectual abilities and skills. These have to do with the mental abilities of the brain.

AFFECTIVE DOMAIN (feelings, emotions and behaviour, ie., attitude, or ’feel’)

Krathwohl’s affective domain taxonomy is perhaps the best known of any of the affective taxonomies. “The taxonomy is ordered according to the principle of internalization. Internalization refers to the process whereby a person’s affect toward an object passes from a general awareness level to a point where the affect is ‘internalized’ and consistently guides or controls the person’s behavior .

Psychomotor domain (manual and physical skills, ie., skills, or ’do’)

Psychomotor objectives are those specific to discreet physical functions, reflex actions and interpretive movements. Traditionally, these types of objectives are concerned with the physically encoding of information, with movement and/or with activities where the gross and fine muscles are used for expressing or interpreting information or concepts. This area also refers to natural, autonomic responses or reflexes.

It means that the instructional objectives make performance skills more prominent. The psychomotor domain has to do with muscular activities.

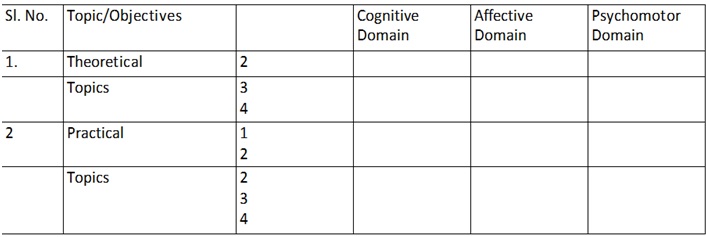

The syllabus is a means to attain the objectives. If aims and means are not in consonance, then the desirable outcomes would only be a pipedream. The utility of the syllabus depends on the fact whether the topics included in it are helpful in the realization of the concerned teaching objectives. In this context, it would be necessary to evaluate the syllabus. The following table can be used

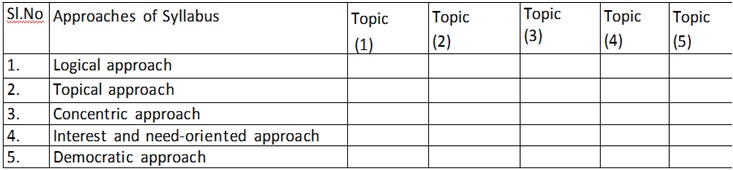

Selection of Organization of Syllabus : The selection of syllabus is the second most important test on the basis of which critical analysis should be conducted. The details of syllabus organisation can be used in the following table beneficially:

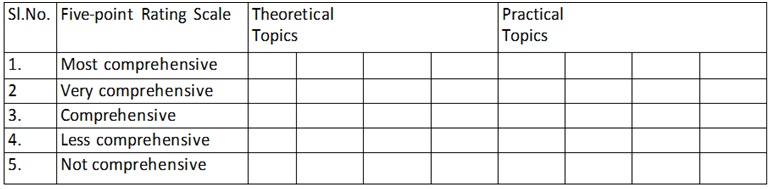

Comprehensiveness of Syllabus : The selection of the syllabus should be as per the level of students. So, the subject matter included in the topics should be neither floating nor deep.

Comprehensiveness is a qualitative concept. So, it will have to be evaluated in a relative manner. For it, a rating scale will have to be used. If common analysis has to be conducted, then the three-point rating scale should be used, and if more intensive study has to be carried out, then five-point rating scale should be desirable.

Data in the above table can be given numerical value in order to calculate comprehensiveness of the syllabus, (for it, all tallies of most comprehensive should be multiplied by 5, very comprehensive by 4, comprehensive by 3, less comprehensive by 2 and not comprehensive by 1, and thus calculate relative comprehensiveness.

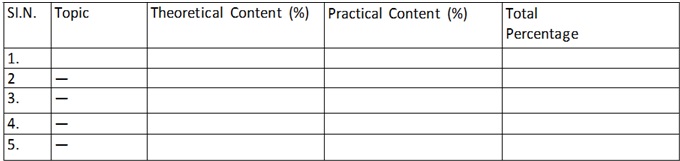

Theoretical, Practical or Both : Both theoretical and practical aspects of science are equally important. If the syllabus is only theoretical, it would make the syllabus bookish and abstract. Due to this, the content in different topics would have to be analysed to see how much theoretical aspect it contains and what practical possibilities exist in it. This can be analysed objectively as follows :

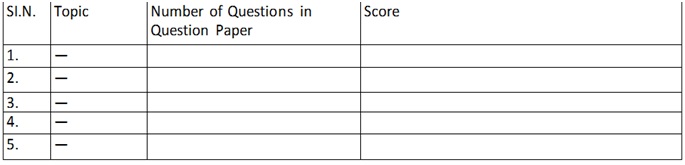

Examination-centered : For both students and teachers, the importance of a topic is determined on the basis of its importance in the examinations. The amount of emphasis of a topic varies with the value of the topic from examination viewpoint for both teachers and students. It has influenced to such extent that the number of marks allotted for each topic are given in the syllabus itself. The analysis of examination effect can be done by the following table :

Child-centered : The syllabus should not only be meant for common students, but it should have due provisions for talented and backward students also. The syllabus should be analyzed from this viewpoint also.

The focal point of the syllabus should be the student. The syllabus should be selected keeping in view the age, previous knowledge, interest, aptitude, needs etc. of students. It should be found out the importance given to these factors in the syllabus. It would only be possible to evaluate its utility for students.

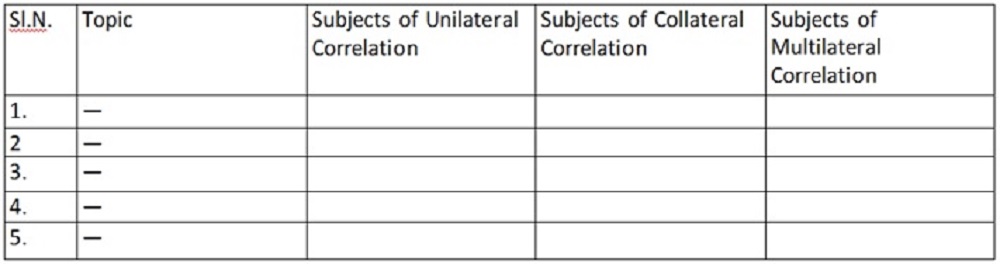

Correlation: Because a student attains knowledge as a whole unit, so the importance of science being related with other subjects, its influence or other subjects and influence of other subjects on it cannot be ignored. Therefore, it should be known whether the form of syllabus is partial or not, which can be done on the basis of the following table:

For Future Education: The syllabuses for the secondary level and higher education should be inter-connected, so that continuity of knowledge can be maintained. The syllabus should be analyzed on this basis by which it can be ascertained which topics can form the basis for future higher education, so that the capability of the syllabus in view of can be evaluated.

Although no one, and no teacher, can predict the future with any certainty, people in leadership capacities such as teachers are required to make guesses about the probable future and plan appropriately. Teachers therefore need to plan their curriculum according to the more likely future their students face while at the same time acknowledging that the students have a future. The competent leader cannot plan according to past successes, as if doing so will force the past to remain with him. The most competent leader and manager, in fact, is not even satisfied with thoughts of the future, but is never satisfied, always sure that whatever is being done can be improved.

REFERANCES

Barrow, R. (1984) Giving Teaching back to Teachers. A critical introduction to curriculum theory, Brighton: Wheatsheaf Books.

Blenkin, G. M. et al (1992) Change and the Curriculu,, London: Paul Chapman.

Dewey, J. (1902) The Child and the Curriculum, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Heineman. Tyler, R. W. (1949) Basic principles of curriculum and instruction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Jeffs, T. J. and Smith, M. K. (1999) Informal Education. Conversation, democracy and learning, Ticknall: Education Now.

Kelly, A. V. (1983; 1999) The Curriculum. Theory and practice 4e, London: Paul Chapman.

Stenhouse, L. (1975) An introduction to Curriculum Research and Development, London: Heineman.

Tyler, R. W. (1949) Basic Principles of Curriculum and Instruction, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.