Dr. V.K.Maheshwari, M.A(Socio, Phil) B.Se. M. Ed, Ph.D

Former Principal, K.L.D.A.V.(P.G) College, Roorkee, India

This period of 900 years from 322 B.C. to 600 A.D. is full of philosophical excitement and innovation. Philosophers transformed old problems and introduced new ones, in such a way as to turn the subject in fresh directions. Much that we encounter in modern philosophy takes its character from the developments of this time. Seventeenth and eighteenth century philosophy cannot be fully understood without it. Since the history of philosophy is a continuous story, this period in its turn cannot be fully understood without some knowledge of Plato and Aristotle. It connects well with the Medieval Philosophy paper, which from 2001 will include Islamic, as well as Latin Medieval Philosophy

This period of 900 years from 322 B.C. to 600 A.D. is full of philosophical excitement and innovation. Philosophers transformed old problems and introduced new ones, in such a way as to turn the subject in fresh directions. Much that we encounter in modern philosophy takes its character from the developments of this time. Seventeenth and eighteenth century philosophy cannot be fully understood without it. Since the history of philosophy is a continuous story, this period in its turn cannot be fully understood without some knowledge of Plato and Aristotle. It connects well with the Medieval Philosophy paper, which from 2001 will include Islamic, as well as Latin Medieval Philosophy

The value of the study of the history of philosophy ought to be apparent. Intelligent persons are . interested in the fundamental problems of existence and in the answers which the human race has sought to find for them on the various stages of civilization. Besides, such a study helps men to understand their own and other times; it throws light on the ethical, religious, political, legal, and economic conceptions of the past and the present, by revealing the underlying principles on which these are based. It likewise serves as a useful preparation for philosophical speculation; passing, as it does, from the simpler to the more complex and difficult constructions of thought, it reviews the philosophical experience of the race and trains the mind in abstract thinking. In this way we are aided in working out our own views of the world and of life. The man who tries to construct a system of philosophy in absolute independence of the work of his predecessors cannot hope to rise very far beyond the crude theories of the beginnings of civilization.

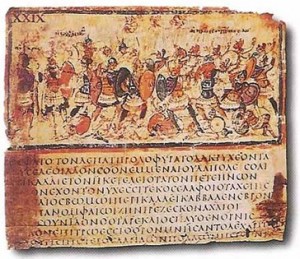

By the history of Greek philosophy we mean the intellectual movement which originated and developed in the Hellenic world, Greek philosophy begins with an inquiry into the essence of the objective world. It is, at first, largely interested in external nature (philosophy of nature), and only gradually turns its eye’ inward, on man himself, or becomes humanistic. The first great problem is: “What is nature and, therefore, man? the second: What is man and, therefore, nature? The shifting of the interest from nature to man leads to the study of human-mental problems, the study of the human mind and human conduct, the study of logic, ethics, psychology, politics, poetics. The attention is next centered, more particularly, upon the ethical problem what is the highest good, what is the end and aim of life? Ethics is made the main issue; logic and metaphysics are studied as aids to the solution of the moral question. Finally, the problem of God and man’s relation to him, the theological problem, is pushed into the foreground, and Greek philosophy ends, as it began, in religion.

Ancient Greek philosophy may be divided into the pre-Socratic period, the Socratic period, and the post-Aristotelian period. The pre-Socratic period was characterized by metaphysical speculation, often preserved in the form of grand, sweeping statements, such as “All is fire”, or “All changes”. Important pre-Socratic philosophers include Thales, Anaximander, Anaximenes, Democritus, Parmenides, and Heraclitus. The Socratic period is named in honor of the most recognizable figure in Western philosophy, Socrates, who, along with his pupil Plato, revolutionized philosophy through the use of the Socratic method, which developed the very general philosophical methods of definition, analysis, and synthesis. While Socrates wrote nothing himself, his influence as a “skeptic” survives through Plato’s works. Plato’s writings are often considered basic texts in philosophy as they defined the fundamental issues of philosophy for future generations. These issues and others were taken up by Aristotle, who studied at Plato’s school, the Academy, and who often disagreed with what Plato had written. The post-Aristotelian period ushered in such philosophers as Euclid, Epicurus, Chrysippus, Hipparchia the Cynic, Pyrrho, and Sextus Empiricus.

Pre-Sophistic period,

The first great problem was taken up in what we may call the Pre-Sophistic period, which extends, let us say, from about 585 to the middle of the fifth century B.C. The earliest Greek philosophy is naturalistic. its attention is directed to nature , it is mostly hylozoistic.it conceives nature as animated or alive ; it is ontological .it inquiries into the essence of things, it is mainly monistic , it seeks to explain its phenomena by means of a single principle ,it is dogmatic : it naively presupposes the competency of the human mind to solve the world-problem. The scene of the philosophy of this period is the colonial world, it flourishes in Ionia, Southern Italy, and Sicily.

The Pre-Sophistic were the first philosophers of the West. They found a way to break out of the reigning mythic mentality and sought to explain nature rationally by means of speculative principles of various kinds generated on the basis of critical observationof the world. Because of this, and because they originated in Milesia on the island of Ionia, the earliest of them are sometimes called Milesian physicists.

This shift from mythic to rational mentality can be characterized as a movement from Who? and Why? questions about the cosmos to What? and How? questions. This shift occurred in part as a side-effect of frustration with the irreconcilable conflict of answers to Who? and Why? questions that were encountered on a regular basis in the trading city of Milesia, where cosmogonic myths would have been swapped along with goods.

The Pre-Sophistic explanations of nature assumed that there were four basic elements (as compared with our much more extensive list of basic elements): earth, water, air, and fire. Their quest to explain nature had to account for these elements as well as the objects and process in nature that these elements made possible.

It can be argued that the Pre-Sophistic bequeathed a number of basic issues to subsequent philosophy.

1. The Problem of the Ultimate Nature of Reality- This problem can be expressed with the following question: What is the ultimate nature of reality, and how can we find out this ultimate nature?

2. The Problem of the Constituents of Ultimate Reality- This problem can be expressed with the following question: What kinds of things, ultimately, are in reality

3. The Problem of Humanity and Ultimate Reality- This problem can be expressed with the following question: How do human affairs relate to ultimate reality?

The Pre-Sophistic quest to answer the What? and How? questions can be understood to have taken four basic directions.

1. Quest for material principle that explains nature

Thales (c.585, Milesia): water is the fundamental material principle that divides to produce the diversity of natural objects and processes.

Anaximander (c.611-547, Milesia): the apeiron (non-perceptible ultimate) is the fundamental material principle that separates into hot and cold, wet and dry, to form the diversity of natural objects and processes.

Anaximenes (c.550, Milesia): air is the fundamental material principle that divides to produce the natural diversity of the cosmos.

Heraclitus (c.500): fire is the fundamental material principle, which allows speaking of nature as a dynamic process developing within tensions of opposites. Heraclitus said, “you cannot step twice into the same river”.

2. Quest for one formal principle that explains nature

Pythagoras (c.570-c.500): religious leader, mathematician, wrestler, musician, healer, philosopher. He founded a secret society whose members believed the cosmos to be a mathematical-musical harmony.

Parmenides (c.500, Elea): reality is one, eternal, unchanging. From this it follows that the world of appearances is illusory and that the ultimate is non-sensible, reachable only by pure thought and argument (this proved to be a crucial influence upon Plato). Parmenides’ student, Zeno, elaborated famous arguments for his teacher’s viewpoint.

3. Quest for plurality of principles that explain nature

Empedocles (c.490-430): the four elements (fire, air, water, earth) combine or divide (through the basic principles of love and strife) to produce the order and chaos of nature as we experience it.

Democritus (c.460-380): the basic constituents of reality are numerous microscopic, solid, varied, indivisible atoms; these atoms collide in the void of space and accumulate to make the objects and processes of nature.

4. Quest for teleological principles that explain nature

Anaxagoras (c.500-428): “Mind” outside of the cosmos forms a lump of matter that is not distinguished into parts. After this initial originating event, the objects of the ordered cosmos result from natural changes requiring no special Mind-intervention (rather than being Mind-made substances).

Diogenes (c.470): Anaximenes’ air is Anaxagoras’ Mind, or intelligence; it enlivens all things. The world is optimally ordered because Mind is its fundamental principle.

The period of the Sophists

The period of the Sophists, who belong to the fifth century, is a period of transition. It shows a growing distrust of the power of the human mind to solve the world-problem and a corresponding lack of faith in traditional conceptions and institutions. This movement is skeptical, radical, revolutionary, indifferent or antagonistic to metaphysical speculation; in calling attention to the problem of man, however, it makes necessary a more thorough examination of the problem of knowledge and the problem of conduct, and ushers in the Socratic period. Athens is the home of this new enlightenment and of the great schools of philosophy growing out of it.

Protagoras ( 490-421) B.C. was the most famous of the Sophists, who were free-enterprise, itinerant teachers of philosophy; it is difficult to be sure about their teachings, and its is highly likely that their teachings were greatly varied, as already mentioned. However, there appear to be several theses—moderated aspects of the famous caricature of Sophism—to which Protagoras was committed.

Phenomenalism: Protagoras attempted to explain reality in terms of the world of appearances, with all of its contradictions. He thought observation of those appearances was a more trustworthy way of finding out about ultimate reality than pure reason, unaided by experience. Thus he rejected those elements of the pre-Socratic quest for deep explanations that tried to penetrate behind the veil of appearances. So, for example, he probably would have thought the Eleatic philosophers absurd, obsessed with a vain goal, deluded by their own infatuation of the powers of reason. There is simply not much point in trying to press beyond appearances, because human reason is an unreliable guide. This low view of human reason corresponds to a generally skeptical view of human moral and intellectual capacity.

Relativism: Because access to ultimate reality is not possible or practical for human reason, it is necessary to regard moral, aesthetic and political value as determined not by nature but by convention. Thus the famous phrase, “man is the measure of all things.”

Democracy: On the one hand, virtue and political wisdom so understood can be taught to a considerable extent, and indeed must be taught if it is to be possessed at all, so the right to rule cannot be awarded on the basis of wealth or birth or social position. On the other hand, humans are notoriously corrupt, so the best way to protect societies from the tendency toward corruption of its rulers is to adopt a democratic political policy. It might be messy, but it is more resilient to corruption because power is distributed widely in a democracy. Power might corrupt, but absolute power corrupts absolutely, and this state of affairs is very likely given the natural depravity of human beings.

Sophists thought that thinking about this problem of the one and the many was a waste of time, and so you have to be content with the irreducible plurality of the world of appearances. They believe that it was vain to try to sort out this dilemma; you have to be content with the apparent flux of reality.

Sophists thought that the sensible, the experience-able, had to be the ultimate guide for human understanding of reality, and that there was no point speculating on the origin of order and chaos, and that equilibrium of individual life and human society was achieved when and so long as human beings made it so.

The humans could know because their experience gave them information about the world. This also indicates the reasons for the limits that exist on the human capacity to know reality, and the happy person was the one who was self-contained, who could take fair advantage of society’s goods to secure his or her needs and desires.

Sophists believes that society was responsible for delivering human beings from savagery and chaos, and that it was steadily evolving through its production of goods and culture. Avoiding the collapse of this evolution is achieved with highest probability when government is democratic.

The Socratic period

The Socratic period, which extends from 430 to 320 B.C. is a period of reconstruction. Socrates was an inspiring philosopher, the teacher of Plato for probably 20 years, and a ceaseless seeker after truth and goodness, according to Plato.

Socrates’ influence is measured especially through Plato, his most famous pupil, who often makes Socrates a character in his dialogues, usually expressing Plato’s point of view (though not always). In the Republic, Socrates is the ideal human, the philosopher-archetype for humanity, an illustration of the key to personal happiness and social justice.

Though reputedly a brilliant dialectician, like the Sophists, Socrates opposed receiving money for his teaching as they did (he probably didn’t need the cash like the Sophists did!). He thought Sophists were not truth-seekers because of their phenomenalism and relativism.

By contrast with Protagoras, Socrates thought that ultimate reality was deceptive at the level of appearances, but that reason, freed from its indebtedness to experience, could penetrate the veil of appearances to discern the form of ultimate reality that lies beyond. This optimistic estimate of human reason corresponds to an optimistic view of the ability of humans to secure happiness and social justice through education in philosophy: the unreflective life is not worth living.

Socrates defends knowledge against the assaults of skepticism, and shows how truth may be reached by the employment of a logical method. He also paves the way for a science of ethics by his efforts to define the meaning of the good. Plato and Aristotle build upon the foundations laid by the master and construct rational theories of knowledge (logic), conduct (ethics), and the State (politics). They likewise work out comprehensive systems of thought (metaphysics), and interpret the universe in terms of mind, or reason, or spirit. We may, therefore, characterize this philosophy as critical: it investigates the principles of knowledge ; as rationalistic : it accepts the competence of reason in the search after truth; as humanistic: it studies man; as spiritualistic or idealistic: it makes mind the chief factor in the explanation of reality. It is dualistic in the sense that it recognizes matter as a secondary factor.

Socrates was suspicious of experience of appearances, and optimistic about the powers of human reason to penetrate those appearances He thought that being was ultimately basic, and becoming a secondary quality of the world of appearances.

Socrates believes that being was ultimately basic, and becoming a secondary quality of the world of appearances. The source of order was the unseen world of forms, and that equilibrium between order and chaos was achieved when society and personal life modeled themselves after the forms

Socrates thought that humans are able to know reality because they bear within themselves the nature of the forms, and a kind of resonance is set up between the world and human understanding, somewhat like remembering. Humans are able to know reality because they bear within themselves the nature of the forms, and a kind of resonance is set up between the world and human understanding, somewhat like remembering.

Socrates thought that the truly happy person is the one who can see the forms, the world of ideas, and so be free of the preliminary, finite concerns and fears of life, and the pure reason could deduce the arrangement of the ideal society, which consisted in a limited aristocracy of education, so that the most gifted would rule and live communally, while others would live according to the laws set by those passing the arduous tests of education

The Post-Aristotelian Period

The last period, the Hellenistic or Post-Aristotelian period of the Ancient era of philosophy comprises many different school of thought developed in the Hellenistic world (which is usually used to mean the spread of Greek culture to non-Greek lands conquered by Alexander the Great in the 4th Century B.C.), which extends from 320 b.c. to 529 a.d., when the Emperor Justinian closed the schools of the philosophers, is called the Post-Aristotelian. The scene is laid in Athens, Alexandria, and Rome. Two phases may be noted, an ethical and a theological one.

(a) The paramount question with Zeno, the Stoic, and Epicurus, the hedonist, is the problem of conduct: What is the aim of rational human endeavor, the highest good? The Epicureans find the answer in happiness; the Stoics in a virtuous life. Both schools are interested in logic and metaphysics: the former, because such knowledge will destroy superstition and ignorance and contribute to happiness; the latter, because it will teach man his duty as a part of a rational universe. The Epicureans are mechanists; according to the Stoics, the universe is the expression of divine reason,

(b) The theological movement, which took its rise in Alexandria, resulted from the contact of Greek philosophy with Oriental religions. In Neo-platonic Era, its most developed form, it seeks

to explain the world as an emanation from a transcendent God who is both the source and the goal of all being.

The loss of political freedom was followed by a period of torpor of the creative energies of the Greek mind Speculation, in the highest sense of constructive effort, was no longer possible and philosophy became wholly practical in its aims. Theoretical knowledge was valued not at all, or only in so far as it contributed to that bracing and strengthening of the moral fiber which men began to seek in philosophy, and for which alone philosophy began to be studied. Philosophy thus came to occupy itself with ethical problems, and to be regarded as a refuge from the miseries of life. All these influences resulted in

(1) a disintegration of the distinctively Greek spirit of philosophy and the substitution of a cosmopolitan spirit of eclecticism;

(2) a centering of philosophical thought around the problems of human life and human destiny; and

(3) the final absorption of Greek philosophy in the reconstructive efforts of the Greco-Oriental philosophers of Alexandria.

But, while metaphysics and physics were neglected in this anthropocentric movement of thought, the mathematical sciences, emancipating themselves from philosophy, began to flourish with new vigor. The astronomers of Sicily and later those of Alexandria stand out of the general gloom of the period as worthy representatives of the Greek spirit of scientific inquiry.

The post-Aristotelian schools of the Roman period were more interested in practical, moral matters than they were in metaphysical speculation. The old Romans had insisted on attention to character and a code of living to build that character. Now that the ideal of the old Roman Republic had been replaced, it was the calling of philosophers to come up with a code for living. With this emphasis on practical and moral standards of living, philosophy gained more popular appeal among the cultured classes of the Hellenistic-Roman world.

The principal schools of this period are:

(a) Stoicism

(b) Skepticism

(c) Epicureanism

(d) Neo-Platonism

Stoicism

Stoicism was by far the most systematic and influential of the Hellenistic schools, yet all the textual evidence for its earliest and philosophically most rigorous period is fragmentary and deficient. Where Socrates seems to have held that the condition of the soul was incomparably more important than that of the body, while bodily health was yet a significant (conditional) good, the Cynics and Stoics alike professed utter indifference to the body, maintaining that virtue of soul was not only necessary but sufficient for happiness. Zeno’s researches in physics, ethics and especially logic were consolidated and extended by the third head of the Stoic school, Chrysippus (280-207 BC), the most important of the Stoics, the loss of whose voluminous writings may well be the most tragic deficiency in the transmission of antique philosophy to modern times.

Stoic philosophy absorbed influences as diverse as Parmenides, Heraclitus, Democritus, Aristotle and the Cynics into its own original outlook with such ingenuity that it became a byword for philosophical systematicity, and was so far from being a contrived amalgam to have provided a natural-seeming guide to life for many subsequent generations of well-born Greeks and Romans, including Cicero and Seneca.

Skepticism

To be skeptical is to cast doubt; to deny that what others claim to be known, can be known. Radical philosophical skepticism attempts to adopt such an attitude toward all knowledge-claims without exception. This kind of skepticism was first formulated in the ancient world, by Pyrrho (365-270 BC) and by Arcesilaus (316-242 BC),.

(A) Pyrrhonian skepticism

Pyrrhonian skepticism takes its name from Pyrrho of Elis, the founder of Greek skepticism Like almost every Greek philosophical outlook, Pyrrhonist was eudaemonist; that is, it supposed that the highest good was eudemonia or human well-being .It identified eudemonia with tranquility or freedom from disturbance (ataraxia). This in turn was held to result only from the suspension of belief (epochê) attendant upon the impression that the appearances warranted no claims to knowledge.

Recent work by M Burnyeat has drawn attention to the ways in which Pyrrhonian skepticism differs from modern forms of skepticism made possible by Descartes. Most importantly,

(i) Descartes’ revolutionary conception of the mind drew the distinction between appearance and reality in a completely new way: what had counted for the ancients as “how things appear” became, for Descartes, elements of an immediately known inner mental reality; and

(ii) the Pyrrhonists put their epistemic theorizing in the service of an ethical purpose in a characteristically Greek way: the whole point, in the end, was the attainment of ataraxic and thereby of eudemonia. Descartes is quite explicit in divorcing his skeptical arguments from any practical considerations.

(B) Academic skepticism

The other strain of ancient skepticism takes its name from Plato’s Academy. It tended to claim descent less from Platonic doctrine than from the results of the Socratic elenchus which were indeed skeptical. But the tradition’s founder, Arcesilaus (316-242 BC) generalized Socratic skepticism: like Pyrrho, who may well have influenced him, he purported to reject all knowledge claims,

Recent scholarly opinion has it that Academic skepticism until the first century BC had much in common with Pyrrhonist: most importantly, a refusal to endorse any knowledge-claims whatsoever, including the claim that nothing can be known. But under the headship of Philo of Larissa (159-84 BC) the Academy became much more moderate, particularly in its opposition to Stoicism .It was partly in response to this rapprochement that Aenesidemus defected from the Academy and revived Pyrrhonism.

Epicureanism

Epicurus (341-271 BC). Epicurean ethics and cosmology have so much in common with Stoicism that it is tempting to see the hostile attitude of many Stoics (Cicero and Plutarch loathed Epicureanism) as an instance of the special enmity reserved for closely-aligned factions in fact Epicurus and his followers so much tempered their philosophical hedonism, according to which pleasure is the only thing good in itself, with rigorous prudential calculation that their conception of the good life ended up very close to an asceticism more usually associated with the Cynics, and indeed with the Stoics themselves. (In this the Epicurean position resembles that set out by Socrates, almost certainly insincerely, toward the end of Plato’s Protagoras.)

De Rerum Natura, Lucretius’s virtuosic Latin hexameter epic written at least two centuries after Epicurus’s death, contains the most influential presentation of Epicurus’s celebrated argument that death is not to be feared: roughly: since we cease to exist at death, the “state” of death cannot be counted an evil for us because it is literally nothing, having no subject to characterize. This argument, or rather its conclusion, was crucial to Epicurean ethics, in that ubiquitous unhappiness was diagnosed as a result of the ambitions, frustrations and anxieties born of a misconceived fear of death. Conversely, happiness (eudemonia) was identified with tranquility (ataraxia) – an identification common to Pyrrhonian skepticism.

Epicurus’s physics, again like the Stoics’, is materialistic – atomistic, in fact, as Epicurus seems to have modified the cosmology of Democritus only to the extent he believed necessary to accommodate the criticisms of Aristotle.

Neo-Platonism

Neo-Platonism is the tradition, founded by Plotinus (205-271 AD), of reformulating Platonic doctrine, with major modifications and accretions partly designed to accommodate criticisms of Aristotle and the Stoics.

(a) Plotinus and pagan Neo-Platonism

The highest principle of the Plotinian system is the One, which is strictly ineffable and eludes any characterization. All modes of being are “emanations” of the One. These form a hierarchy. The perfection of a mode of being is correlated with its degree of unity, and (what coincides with this) with its independence from the spatiotemporal order. The highest mode is the “World-mind” (nous), which shares many features of Aristotle’s unmoved mover and contains the Platonic Forms as elements. Next is the “World-soul” (psuchê), which creates time and space through its discursive thought. Nature (phusis) is the lowest creative principle, corresponding to the Stoic World-soul Bare matter is the lowest possible mode of being.

The asceticism and mysticism characteristic of Plato’s middle period are especially pronounced in Plotinus. The perfection of the soul requires a turning-away from material nature, through intellectual self-purification. The utmost mental discipline might yield a glimpse of ecstasy, wherein the soul is fleetingly identified with the supreme unity of the One.

(b) St Augustine and Christian Neo-Platonism

Augustine was born in Thagaste, in Algeria, in 354, A.D .The philosophy he unsystematically expounded in some of these works is an ingenious synthesis of neo-platonic and Christian doctrine. God plays the role of the Plutonian One, and an understanding of his reality and nature can only be attained by the divine illumination attendant upon an act of faith.

“Do not spoil what you have by desiring what you have not; remember that what you now have was once among the things you only hoped for.”

Epicurus quotes (Greek philosopher, BC 341-270)