Dr. V.K. Maheshwari, Former Principal

K.L.D.A.V (P. G) College, Roorkee, India

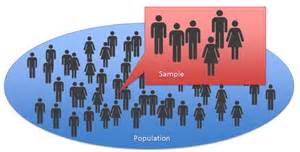

Surveys are consistently used to measure quality. For example, surveys might be used to gauge customer perception of product quality or quality performance in service delivery.

Statisticians have generally grouped data collected from these surveys into a hierarchy of four levels of measurement:

1. Nominal data: The weakest level of measurement representing categories without numerical representation.

2. Ordinal data: Data in which an ordering or ranking of responses is possible but no measure of distance is possible.

3. Interval data: Generally integer data in which ordering and distance measurement are possible.

4. Ratio data: Data in which meaningful ordering, distance, decimals and fractions between variables are possible.

Data analyses using nominal, interval and ratio data are generally straightforward and transparent. Analyses of ordinal data, particularly as it relates to Likert or other scales in surveys, are not. This is not a new issue. The adequacy of treating ordinal data as interval data continues to be controversial in survey analyses in a variety of applied fields.1,2

An underlying reason for analyzing ordinal data as interval data might be the contention that parametric statistical tests (based on the central limit theorem) are more powerful than nonparametric alternatives. Also, conclusions and interpretations of parametric tests might be considered easier to interpret and provide more information than nonparametric alternatives.

However, treating ordinal data as interval (or even ratio) data without examining the values of the dataset and the objectives of the analysis can both mislead and misrepresent the findings of a survey. To examine the appropriate analyses of scalar data and when its preferable to treat ordinal data as interval data, we will concentrate on Likert scales.

What is a rating scale?

A rating scale is a tool used for assessing the performance of tasks, skill levels, procedures, processes, qualities, quantities, or end products, such as reports, drawings, and computer programs. These are judged at a defined level within a stated range. Rating scales are similar to checklists except that they indicate the degree of accomplishment rather than just yes or no.

Rating scales list performance statements in one column and the range of accomplishment in descriptive words, with or without numbers, in other columns. These other columns form “the scale” and can indicate a range of achievement, such as from poor to excellent, never to always, beginning to exemplary, or strongly disagree to strongly agree.

What’s the definition of Likert scale?

According to Wikipedia: “A rating scale is a set of categories designed to elicit information about a quantitative or a qualitative attribute. In the social sciences, common examples are the Likert scale and 1-10 rating scales in which a person selects the number which is considered to reflect the perceived quality of a product.”

“Rating scales are used quite frequently in survey research and there are many different kinds of rating scales. A typical rating scale asks subjects to choose one response category from several arranged in hierarchical order. Either each response category is labeled or else only the two endpoints of the scale are “anchored.

By definition Rating scales are survey questions that offer a range of answer options — from one extreme attitude to another, like “extremely likely” to “not at all likely.” Typically, they include a moderate or neutral midpoint.

Likert scales (named after their creator, American social scientist Rensis Likert) are quite popular because they are one of the most reliable ways to measure opinions, perceptions, and behaviors.

Compared to binary questions, which give you only two answer options, Likert-type questions will get you more granular feedback about whether your product was just “good enough” or (hopefully) “excellent.” They can help decide whether a recent company outing left employees feeling “very satisfied,” “somewhat dissatisfied,” or maybe just neutral.

This method will let you uncover degrees of opinion that could make a real difference in understanding the feedback you’re getting. And it can also pinpoint the areas where you might want to improve your service or product.

Characteristics of rating scales

Rating scales should:

• have criteria for success based on expected outcomes

• have clearly defined, detailed statements

This gives more reliable results.

For assessing end products, it can sometimes help to have a set of photographs

or real samples that show the different levels of achievement. Students can

visually compare their work to the standards provided.

• have statements that are chunked into logical sections or flow sequentially

• include clear wording with numbers when a number scale is used

As an example, when the performance statement describes a behaviour or quality,

1 = poor through to 5 = excellent is better than 1 = lowest through to 5 = highest

or simply 1 through 5.

The range of numbers should be the same for all rows within a section (such as

all being from 1 to 5).

The range of numbers should always increase or always decrease. For example, if

the last number is the highest achievement in one section, the last number should

be the highest achievement in the other sections.

• have specific, clearly distinguishable terms

Using good then excellent is better than good then very good because it is

hard to distinguish between good and very good. Some terms, such as often or

sometimes, are less clear than numbers, such as 80% of the time.

- be reviewed by other instructors

- be short enough to be practical

- have space for other information such as the student’s name, date, course, examiner, and overall result

- highlight critical tasks or skills

- indicate levels of success required before proceeding further, if applicable

- sometimes have a column or space for providing additional feedback

Basic goals for Scale points and their labels

Survey data are only as good as the questions asked and the way we ask them. To that end, let’s talk rating scales.

To get started, let’s outline five basic goals for scale points and their labels:

- It should be easy to interpret the meaning of each scale point

- Responses to the scale should be reliable, meaning that if we asked the same question again, each respondent should provide the same answer

- The meaning scale points should be interpreted identically by all respondents

- The scale should include enough points to differentiate respondents from one another as much as validly possible

- The scale’s points should map as closely as possible to the underlying idea (construct) of the scale

Number of Scale point to be included

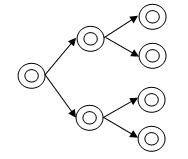

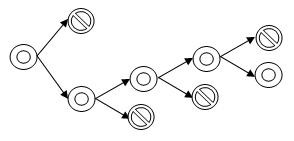

The number of scale points depends on what sort of question you’re asking. If you’re dealing with an idea or construct that ranges from positive to negative – think satisfaction levels – (these are known as bi-polar constructs) then you’re going to want a 7-point scale that includes a middle or neutral point. In practice, this means the response options for a satisfaction question should look like this:

Scale Point 1

If you’re dealing with an idea or construct that ranges from zero to positive – think effectiveness – (these are known as unipolar constructs) then you’ll go with a 5-point scale. The response options for this kind of question would look like this:

Scale Point 2

Since it doesn’t make sense to have negative effectiveness, this kind of five-point scale is the best practice.

Always measure bipolar constructs with bipolar scales and unipolar constructs with unipolar scales.

In short, the goal is to make sure respondents can answer in a way that allows them to differentiate themselves as much as is validly possible without providing so many points that the measure becomes noisy or unreliable. Even on an 11-point (0-10) scale respondents start to have difficulty reliably placing themselves– 3 isn’t so different from 4 and 6 isn’t so different from 7.

Middle Alternative

There is a general complain that including middle alternatives basically allows respondents to avoid taking a position. Some even mistakenly assume that midpoint responses are disguised “Don’t knows” or that respondents are satisficing when they provide midpoint responses.

However, research suggests that midpoint responses don’t necessarily mean that respondents don’t know or are avoiding making a choice. In fact, research indicates that if respondents that select the midpoint were forced to choose a side, they would not necessarily answer the question in the same way as other respondents that opted to choose a side.

This suggests that middle alternatives should be provided and that they may be validly and reliably chosen by respondents. Forcing respondents to take a side may introduce unwanted variance or bias to the data.

Labeling Response options

Some people prefer to only label the end-points. Others will also label the midpoint. Some people label with words and others label numerically. What’s right?

The most accurate surveys will have a clear and specific label that indicates exactly what each point means. Going back to the goals of scale points and their labels, we want all respondents to easily interpret the meaning of each scale point and for there to be no room for different interpretations between respondents. Labels are key to avoiding ambiguity and respondent confusion.

This means that partially labeled scales may not perform as well as a fully labeled scale and that numbers should only be used for scales collecting numeric data (not rating scales).

Common Rating Scales

One of the most frequent mistakes when reviewing questionnaires are poorly written scales. Novice survey authors often create their own scale rather than using the appropriate common scale. It’s hard to write a good scale; instead by better off rewording question slightly use one of the following.

- Acceptability Not at all acceptable, Slightly acceptable, Moderately acceptable, Very acceptable, Completely acceptable

- Agreement Completely disagree, Disagree, Somewhat disagree, Neither agree nor disagree, Somewhat agree, Agree, Completely agree

- Appropriateness Absolutely inappropriate, Inappropriate, Slightly inappropriate, Neutral, Slightly appropriate, Appropriate, Absolutely appropriate

- Awareness Not at all aware, Slightly aware, Moderately aware, Very aware, Extremely aware

- Beliefs Not at all true of what I believe, Slightly true of what I believe, Moderately true of what I believe, Very true of what I believe, Completely true of what I believe

- Concern Not at all concerned, Slightly concerned, Moderately concerned, Very concerned, Extremely concerned

- Familiarity Not at all familiar, Slightly familiar, Moderately familiar, Very familiar, Extremely familiar

- Frequency Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often, Always

- Importance Not at all important, Slightly important, Moderately important, Very important, Extremely important

- Influence Not at all influential, Slightly influential, Moderately influential, Very influential, Extremely influential

- Likelihood Not at all likely, Slightly likely, Moderately likely, Very likely, Completely likely

- Priority Not a priority, Low priority, Medium priority, High priority, Essential

- Probability Not at all probable, Slightly probable, Moderately probable, Very probable, Completely probable

- Quality Very poor, Poor, Fair, Good, Excellent

- Reflect Me Not at all true of me, Slightly true of me, Moderately true of me, Very true of me, Completely true of me

- Satisfaction (bipolar) Completely dissatisfied, Mostly dissatisfied, Somewhat dissatisfied, Neither satisfied or dissatisfied, Somewhat satisfied, Mostly satisfied, Completely satisfied

- Satisfaction (unipolar) Not at all satisfied, Slightly satisfied, Moderately satisfied, Very satisfied, Completely satisfied

This list follows Krosnick’s advice to use 5-point unipolar scales and 7-point bipolar scales.

Types of rating scales

Some time more than one rating scale question is required to measure an attitude or perception due to the requirement for statistical comparisons between the categories in the polytomous Rasch model for ordered categories. In terms of Classical test theory, more than one question is required to obtain an index of internal reliability such as Cronbach’s alpha, which is a basic criterion for assessing the effectiveness of a rating scale and, more generally, a psychometric instrument.

All rating scales can be classified into one or two of three types:

- numeric rating scale

- graphic rating scale

- Descriptive graphic rating scale

Considerations for numeric rating scales

If you assign numbers to each column for marks, consider the following:

• What should the first number be? If 0, does the student deserve 0%? If 1, does the student deserve 20% (assuming 5 is the top mark) even if he/she has done extremely poorly?

• What should the second number be? If 2 (assuming 5 is the top mark), does the person really deserve a failing mark (40%)? This would mean that the first two or three columns represent different degrees of failure.

• Consider variations in the value of each column. Assuming 5 is the top mark, the columns could be valued at 0, 2.5, 3, 4, and 5.

• Consider the weighting for each row. For example, for rating a student’s report, should the introduction, main body, and summary be proportionally rated the same? Perhaps, the main body should be valued at five times the amount of the introduction and summary. A multiplier or weight can be put in another column for calculating a total mark in the last column.

Consider having students create the rating scale. This can get them to think deeply about the content.

Graphic Rating Scale

Graphic Rating Scale is a type of performance appraisal method. In this method traits or behaviours that are important for effective performance are listed out and each personis rated against these traits.

The method is easy to understand and is user friendly.Standardization of the comparison criteria’s Behaviours are quantified making appraisal system easier

Ratings are usually on a scale of 1-5, 1 being Non-existent, 2 being Average, 3 being Good, 4 being Very Good and 5 being Excellent.

Characteristics of a good Graphic Rating scale are:

• Performance evaluation measures against which an employee has to be rated must be well defined.

• Scales should be behaviorally based.

• Ambiguous behaviors definitions, such as loyalty, honesty etc. should be avoided

• Ratings should be relevant to the behaGraphic Rating Scale

Graphic Rating Scale is a type of performance appraisal method. In this method traits or behaviours that are important for effective performance are listed out and each personis rated against these traits.

The method is easy to understand and is user friendly.Standardization of the comparison criteria’s Behaviours are quantified making appraisal system easier

Ratings are usually on a scale of 1-5, 1 being Non-existent, 2 being Average, 3 being Good, 4 being Very Good and 5 being Excellent.

Characteristics of a good Graphic Rating scale are:

• Performance evaluation measures against which an employee has to be rated must be well defined.

• Scales should be behaviorally based.

• Ambiguous behaviors definitions, such as loyalty, honesty etc. should be avoided

• Ratings should be relevant to the behavior being measured.

But in this scale, rating behaviors may or may not be accurate as the perception of behaviors might vary with judges. Rating against labels like excellent and poor is difficult at times even tricky as the scale does not exemplify the ideal behaviors required for a achieving a rating. Perception error like Halo effect, Recency effect, stereotyping etc. can cause incorrect rating. behavior being measured.

But in this scale ,rating behaviors may or may not be accurate as the perception of behaviors might vary with judges. Rating against labels like excellent and poor is difficult at times even tricky as the scale does not exemplify the ideal behaviours required for a achieving a rating. Perception error like Halo effect, Recency effect, stereotyping etc. can cause incorrect rating.

Some data are measured at the ordinal level. Numbers indicate the relative position of items, but not the magnitude of difference. Attitude and opinion scales are usually ordinal; one example is a Likert response scale

Some data are measured at the interval level. Numbers indicate the magnitude of difference between items, but there is no absolute zero point. A good example is a Fahrenheit/Celsius temperature scale where the differences between numbers matter, but placement of zero does not.

Some data are measured at the ratio level. Numbers indicate magnitude of difference and there is a fixed zero point. Ratios can be calculated. Examples include age, income, price, costs, sales revenue, sales volume and market share.

Likert scales are a common ratings format for surveys. Respondents rank quality from high to low or best to worst using five or seven levels.

The Likert Scale

A Likert scale (pronounced /ˈlɪkərt/, also /ˈlaɪkərt/) is a psychometric scale commonly used in questionnaires, and is the most widely used scale in survey research, such that the term is often used interchangeably with rating scale even though the two are not synonymous. When responding to a Likert questionnaire item, respondents specify their level of agreement to a statement. The scale is named after its inventor, psychologist Rensis Likert.

Rensis Likert, the developer of the scale, pronounced his name ‘lick-urt’ with a short “i” sound. It has been claimed that Likert’s name “is among the most mispronounced in [the] field.” Although many people use the long “i” variant (‘lie-kurt’), those who attempt to stay true to Dr. Likert’s pronunciation use the short “i” pronunciation (‘lick-urt’).

Sample question presented using a five-point Likert item

An important distinction must be made between a Likert scale and a Likert item. The Likert scale is the sum of responses on several Likert items. Because Likert items are often accompanied by a visual analog scale (e.g., a horizontal line, on which a subject indicates his or her response by circling or checking tick-marks), the items are sometimes called scales themselves. This is the source of much confusion; it is better, therefore, to reserve the term Likert scale to apply to the summated scale, and Likert item to refer to an individual item.

A Likert item is simply a statement which the respondent is asked to evaluate according to any kind of subjective or objective criteria; generally the level of agreement or disagreement is measured. Often five ordered response levels are used, although many psychometricians advocate using seven or nine levels; a recent empirical study found that a 5- or 7- point scale may produce slightly higher mean scores relative to the highest possible attainable score, compared to those produced from a 10-point scale, and this difference was statistically significant. In terms of the other data characteristics, there was very little difference among the scale formats in terms of variation about the mean, skewness or kurtosis.

The format of a typical five-level Likert item is:

1. Strongly disagree

2. Disagree

3. Neither agree nor disagree

4. Agree

5. Strongly agree

Likert scaling is a bipolar scaling method, measuring either positive or negative response to a statement. Sometimes a four-point scale is used; this is a forced choice method[citation needed] since the middle option of “Neither agree nor disagree” is not available.

Likert scales may be subject to distortion from several causes. Respondents may avoid using extreme response categories (central tendency bias); agree with statements as presented (acquiescence bias); or try to portray themselves or their organization in a more favorable light (social desirability bias). Designing a scale with balanced keying (an equal number of positive and negative statements) can obviate the problem of acquiescence bias, since acquiescence on positively keyed items will balance acquiescence on negatively keyed items, but central tendency and social desirability are somewhat more problematic.

How to write Likert scale survey questions

Be accurate. Likert-type questions must be phrased correctly in order to avoid confusion and increase their effectiveness. If you ask about satisfaction with the service at a restaurant, do you mean the service from valets, the waiters, or the host? All of the above? Are you asking whether the customer was satisfied with the speed of service, the courteousness of the attendants, or the quality of the food and drinks? The more specific you are, the better your data will be.

Be careful with adjectives. When you’re using words to ask about concepts in your survey, you need to be sure people will understand exactly what you mean. Your response options need to include descriptive words that are easily understandable. There should be no confusion about which grade is higher or bigger than the next: Is “pretty much” more than “quite a bit”? It’s advisable to start from the extremes (“extremely,” “not at all”,) set the midpoint of your scale to represent moderation (“moderately,”) or neutrality (“neither agree nor disagree,”) and then use very clear terms–“very,” “slightly”–for the rest of the options.

Bipolar or unipolar? Do you want a question where attitudes can fall on two sides of neutrality–“love” vs. “hate”– or one where the range of possible answers goes from “none” to the maximum? The latter, a unipolar scale, is preferable in most cases. For example, it’s better to use a scale that ranges from “extremely brave” to “not at all brave,” rather than a scale that ranges from “extremely brave” to “extremely shy.” Unipolar scales are just easier for people to think about, and you can be sure that one end is the exact opposite of the other, which makes it methodologically more sound as well.

Better to ask. Statements carry an implicit risk: Most people will tend to agree rather than disagree with them because humans are mostly nice and respectful. (This phenomenon is called acquiescence response bias.) It’s more effective, then, to ask a question than to make a statement.

5 extra tips on how to use Likert scales

- Keep it labeled. Numbered scales that only use numbers instead of words as response options may give survey respondents trouble, since they might not know which end of the range is positive or negative.

- Keep it odd. Scales with an odd number of values will have a midpoint. How many options should you give people? Respondents have difficulty defining their point of view on a scale greater than seven. If you provide more than seven response choices, people are likely to start picking an answer randomly, which can make your data meaningless. Our methodologists recommend five scale points for a unipolar scale, and seven scale points if you need to use a bipolar scale.

- Keep it continuous. Response options in a scale should be equally spaced from each other. This can be tricky when using word labels instead of numbers, so make sure you know what your words mean.

- Keep it inclusive. Scales should span the entire range of responses. If a question asks how quick your waiter was and the answers range from “extremely quick” to “moderately quick,” respondents who think the waiter was slow won’t know what answer to choose.

- Keep it logical. Add skip logic to save your survey takers some time. For example, let’s say you want to ask how much your patron enjoyed your restaurant, but you only want more details if they were unhappy with something. Use question logic so that only those who are unhappy skip to a question asking for improvement suggestions.

You have probably known Likert-scale questions for a long time, even if you didn’t know their unique name. Now you also know how to create effective ones that can bring a greater degree of nuance to the key questions in your surveys.

Basics of Likert Scales

Likert scales were developed in 1932 as the familiar five-point bipolar response that most people are familiar with today.3 These scales range from a group of categories—least to most—asking people to indicate how much they agree or disagree, approve or disapprove, or believe to be true or false. There’s really no wrong way to build a Likert scale. The most important consideration is to include at least five response categories. Some examples of category groups appear in Table 1.

The ends of the scale often are increased to create a seven-point scale by adding “very” to the respective top and bottom of the five-point scales. The seven-point scale has been shown to reach the upper limits of the scale’s reliability.4 As a general rule, Likert and others recommend that it is best to use as wide a scale as possible. You can always collapse the responses into condensed categories, if appropriate, for analysis.

With that in mind, scales are sometimes truncated to an even number of categories (typically four) to eliminate the “neutral” option in a “forced choice” survey scale. Rensis Likert’s original paper clearly identifies there might be an underlying continuous variable whose value characterizes the respondents’ opinions or attitudes and this underlying variable is interval level, at best.5

Analysis, Generalization to Continuous Indexes

As a general rule, mean and standard deviation are invalid parameters for descriptive statistics whenever data are on ordinal scales, as are any parametric analyses based on the normal distribution. Nonparametric procedures—based on the rank, median or range—are appropriate for analyzing these data, as are distribution free methods such as tabulations, frequencies, contingency tables and chi-squared statistics.

Kruskall-Wallis models can provide the same type of results as an analysis of variance, but based on the ranks and not the means of the responses. Given these scales are representative of an underlying continuous measure, one recommendation is to analyze them as interval data as a pilot prior to gathering the continuous measure.

Table 2 includes an example of misleading conclusions, showing the results from the annual Alfred P. Sloan Foundation survey of the quality and extent of online learning in the United States. Respondents used a Likert scale to evaluate the quality of online learning compared to face-to-face learning.

While 60%-plus of the respondents perceived online learning as equal to or better than face-to-face, there is a persistent minority that perceived online learning as at least somewhat inferior. If these data were analyzed using means, with a scale from 1 to 5 from inferior to superior, this separation would be lost, giving means of 2.7, 2.6 and 2.7 for these three years, respectively. This would indicate a slightly lower than average agreement rather than the actual distribution of the responses.

A more extreme example would be to place all the respondents at the extremes of the scale, yielding a mean of “same” but a completely different interpretation from the ac-tual responses.

Under what circumstances might Likert scales be used with interval procedures? Suppose the rank data included a survey of income measuring $0, $25,000, $50,000, $75,000 or $100,000 exactly, and these were measured as “low,” “medium” and “high.”

The “intervalness” here is an attribute of the data, not of the labels. Also, the scale item should be at least five and preferably seven categories.

Another example of analyzing Likert scales as interval values is when the sets of Likert items can be combined to form indexes. However, there is a strong caveat to this approach: Most researchers insist such combinations of scales pass the Cronbach’s alpha or the Kappa test of intercorrelation and validity.

Also, the combination of scales to form an interval level index assumes this combination forms an underlying characteristic or variable.

Steps to Developing a Likert Scale

1. Define the focus: what is it you are trying to measure? Your topic should be one-dimensional. For example “Customer Service” or “This Website.”

2. Generate the Likert Scale items. The items should be able to be rated on some kind of scale. The image at the top of this page has some suggestions. For example, polite/rude could be rated as “very polite”, “polite”, “not polite” or “very impolite.” Politeness could also be rated on a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 is not polite at all and 10 is extremely polite.

3. Rate the Likert Scale items. You want to be sure your focus is good, so pick a team of people to go through the items in step 2 above and rate them as favorable/neutral/unfavorable to your focus. Weed out the items that are mostly seen as unfavorable.

4. Administer your Likert Scale test.

Hypothesis Tests on Likert Scales

If you known that you’re going to be performing analysis on Likert scale data, it’s easier to tailor your questions in the development stage, rather than to collect your data and then make a decision about analysis. What analysis you run depends on the format of your questionnaire.

There is some disagreement in education and research about whether you should run parametric tests like the t-test or non-parametric hypothesis tests like the Mann-Whitney on Likert-scale data. Winter and Dodou(2010) researched this issue, with the following results:

“In conclusion, the t test and [Mann-Whitney] generally have equivalent power, except for skewed, peaked, or multimodal distributions for which strong power differences between the two tests occurred. The Type I error rate of both methods was never more than 3% above the nominal rate of 5%, even not when sample sizes were highly unequal.”

In other words, there seems to be no real difference between the results for parametric and non-parametric tests, except for skewed, peaked, or multimodal distributions. Which avenue you take is up to you, your department, and perhaps the journal you are submitting to (if any). The most important step at the decision stage is deciding if you want to treat your data as ordinal or interval data.

General guidelines:

• For a series of individual questions with Likert responses, treat the data as ordinal variables.

• For a series of Likert questions that together describe a single construct (personality trait or attitude), treat the data as interval variables.

Two Options

Most Likert scales are classified as ordinal variables. If you are 100% sure that the distance between variables is constant, then they can be treated as interval variables for testing purposes. In most cases, your data will be ordinal, as it’s impossible to tell the difference between, say, “strongly agree” and “agree” vs. “agree” and “neutral.”

Ordinal Scale Data

With most variable types (interval, ratio, nominal), you can find the mean. This is not true for Likert scale data. The mean in a Likert scale can’t be found because you don’t know the “distance” between the data items. In other words, while you can find an average of 1,2, and 3, you can’t find an average of “agree”, “disagree”, and “neutral.”

“The average of ‘fair’ and ‘good’ is not ‘fair‐and‐a‐half’; which is true even when one assigns integers to represent ‘fair’ and ‘good’!” – Susan Jamieson paraphrasing Kuzon Jr et al. (Jamieson, 2004)

Statistics Choices

Statistics you can use are:

• The mode: the most common response.

• The median: the “middle” response when all items are placed in order.

• The range and interquartile range: to show variability.

• A bar chart or frequency table: to show a table of results. Do not make a histogram, as the data is not continuous.

Hypothesis Testing

In hypothesis testing for Likert scales, the independent variable represents the groups and the dependent variable represents the construct you are measuring. For example, if you survey nursing students to measure their level of compassion, the independent variable is the groups of nursing students and the dependent variable is the level of compassion.

Types of test you can run:

• Kruskal Wallis: determines if the median for two groups is different.

• Mann Whitney U Test: determines if the medians for two groups are different. Simple to evaluate single Likert scale questions, but suffers from several forms of bias, including central tendency bias, acquiescence bias and social desirability bias. In addition, validity is usually hard to demonstrate.

More Options for Two Categories

If you combine your responses into two categories, for example, agree and disagree, more test options open up to you.

• Chi-square: The test is designed for multinomial experiments, where the outcomes are counts placed into categories.

• McNemar test: Tests if responses to categories are the same for two groups/conditions.

• Cochran’s Q test: An extension of McNemar that tests if responses to categories are the same for three or moregroups/conditions.

• Friedman Test: for finding differences in treatments across multiple attempts.

Measures of Association

Sometimes you want to know if a one group of people has a different response (higher or lower) from another group of people to a certain Likert scale item. To answer this question, you would use a measure of association instead of a test for differences (like those listed above).

If your groups are ordinal (i.e. ordered) in some way, like age-groups, you can use:

• Kendall’s tau coefficient or variants of tau (e.g., gamma coefficient; Somers’ D).

• Spearman rank correlation.

If your groups aren’t ordinal, then use one of these:

• Phi coefficient.

• Contingency coefficient.

• Cramer’s V.

Interval Scale Data

Statistics that are suitable for interval scale Likert data:

• Mean.

• Standard deviation.

Hypothesis Tests suitable for interval scale Likert data:

• T-test.

• ANOVA.

• Regression analysis (either ordered logistic regression or multinomial logistic regression). If you can combine your dependent variables into two responses (e.g. agree or disagree), run binary logistic regression.

Scoring and analysis

After the questionnaire is completed, each item may be analyzed separately or in some cases item responses may be summed to create a score for a group of items. Hence, Likert scales are often called summative scales.

Whether individual Likert items can be considered as interval-level data, or whether they should be considered merely ordered-categorical data is the subject of disagreement. Many regard such items only as ordinal data, because, especially when using only five levels, one cannot assume that respondents perceive all pairs of adjacent levels as equidistant. On the other hand, often (as in the example above) the wording of response levels clearly implies a symmetry of response levels about a middle category; at the very least, such an item would fall between ordinal- and interval-level measurement; to treat it as merely ordinal would lose information. Further, if the item is accompanied by a visual analog scale, where equal spacing of response levels is clearly indicated, the argument for treating it as interval-level data is even stronger.

When treated as ordinal data, Likert responses can be collated into bar charts, central tendency summarised by the median or the mode (but some would say not the mean), dispersion summarised by the range across quartiles (but some would say not the standard deviation), or analyzed using non-parametric tests, e.g. chi-square test, Mann–Whitney test, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, or Kruskal–Wallis test. Parametric analysis of ordinary averages of Likert scale data is also justifiable by the Central Limit Theorem, although some would disagree that ordinary averages should be used for Likert scale data.

Responses to several Likert questions may be summed, providing that all questions use the same Likert scale and that the scale is a defendable approximation to an interval scale, in which case they may be treated as interval data measuring a latent variable. If the summed responses fulfill these assumptions, parametric statistical tests such as the analysis of variance can be applied. These can be applied only when more than 5 Likert questions are summed.

Data from Likert scales are sometimes reduced to the nominal level by combining all agree and disagree responses into two categories of “accept” and “reject”. The chi-square, Cochran Q, or McNemar test are common statistical procedures used after this transformation.

Consensus based assessment (CBA) can be used to create an objective standard for Likert scales in domains where no generally accepted standard or objective standard exists. Consensus based assessment (CBA) can be used to refine or even validate generally accepted standards.

Level of measurement

The five response categories are often believed to represent an Interval level of measurement. But this can only be the case if the intervals between the scale points correspond to empirical observations in a metric sense. In fact, there may also appear phenomena which even question the ordinal scale level. For example, in a set of items A,B,C rated with a Likert scale circular relations like A>B, B>C and C>A can appear. This violates the axiom of transitivity for the ordinal scale.

Rasch model

Likert scale data can, in principle, be used as a basis for obtaining interval level estimates on a continuum by applying the polytomous Rasch model, when data can be obtained that fit this model. In addition, the polytomous Rasch model permits testing of the hypothesis that the statements reflect increasing levels of an attitude or trait, as intended. For example, application of the model often indicates that the neutral category does not represent a level of attitude or trait between the disagree and agree categories.

Again, not every set of Likert scaled items can be used for Rasch measurement. The data has to be thoroughly checked to fulfill the strict formal axioms of the model.

The Likert scale is commonly used in survey research. It is often used to measure respondents’ attitudes by asking the extent to which they agree or disagree with a particular question or statement. A typical scale might be “strongly agree, agree, not sure/undecided, disagree, strongly disagree.” On the surface, survey data using the Likert scale may seem easy to analyze, but there are important issues for a data analyst to consider.

General Instructions

1. Get your data ready for analysis by coding the responses. For example, let’s say you have a survey that asks respondents whether they agree or disagree with a set of positions in a political party’s platform. Each position is one survey question, and the scale uses the following responses: Strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree. In this example, we’ll code the responses accordingly: Strongly disagree = 1, disagree = 2, neutral = 3, agree = 4, strongly agree = 5.

2. Remember to differentiate between ordinal and interval data, as the two types require different analytical approaches. If the data are ordinal, we can say that one score is higher than another. We cannot say how much higher, as we can with interval data, which tell you the distance between two points. Here is the pitfall with the Likert scale: many researchers will treat it as an interval scale. This assumes that the differences between each response are equal in distance. The truth is that the Likert scale does not tell us that. In our example here, it only tells us that the people with higher-numbered responses are more in agreement with the party’s positions than those with the lower-numbered responses.

3. Begin analyzing your Likert scale data with descriptive statistics. Although it may be tempting, resist the urge to take the numeric responses and compute a mean. Adding a response of “strongly agree” to two responses of “disagree” would give us a mean of 4, but what is the significance of that number? Fortunately, there are other measures of central tendency we can use besides the mean. With Likert scale data, the best measure to use is the mode, or the most frequent response. This makes the survey results much easier for the analyst (not to mention the audience for your presentation or report) to interpret. You also can display the distribution of responses (percentages that agree, disagree, etc.) in a graphic, such as a bar chart, with one bar for each response category.

4. Proceed next to inferential techniques, which test hypotheses posed by researchers. There are many approaches available, and the best one depends on the nature of your study and the questions you are trying to answer. A popular approach is to analyze responses using analysis of variance techniques, such as the Mann Whitney or Kruskal Wallis test. Suppose in our example we wanted to analyze responses to questions on foreign policy positions with ethnicity as the independent variable. Let’s say our data includes responses from Anglo, African-American, and Hispanic respondents, so we could analyze responses among the three groups of respondents using the Kruskal Wallis test of variance.

5. Simplify your survey data further by combining the four response categories (e.g., strongly agree, agree, disagree, strongly disagree) into two nominal categories, such as agree/disagree, accept/reject, etc.). This offers other analysis possibilities. The chi square test is one approach for analyzing the data in this way.

Considerations for numeric rating scales

If you assign numbers to each column for marks, consider the following:

• What should the first number be? If 0, does the student deserve 0%? If 1, does the student deserve 20% (assuming 5 is the top mark) even if he/she has done extremely poorly?

• What should the second number be? If 2 (assuming 5 is the top mark), does the person really deserve a failing mark (40%)? This would mean that the first two or three columns represent different degrees of failure.

• Consider variations in the value of each column. Assuming 5 is the top mark, the columns could be valued at 0, 2.5, 3, 4, and 5.

• Consider the weighting for each row. For example, for rating a student’s report, should the introduction, main body, and summary be proportionally rated the same? Perhaps, the main body should be valued at five times the amount of the introduction and summary. A multiplier or weight can be put in another column for calculating a total mark in the last column.

Consider having students create the rating scale. This can get them to think deeply about the content.

Rating scale example : Practicum performance assessment

Expected learning outcome: The student will demonstrate professionalism and high-quality work during the practicum.

Criteria for success: A maximum of one item is rated as “Needs improvement” in each section.

| Performance area |

Needs improvement |

Average |

Above average |

Comments |

| -A. Attitude |

|

|

|

|

| • Punctual |

|

|

|

|

| • Respectful of equipment |

|

|

|

|

| • Uses supplies conscientiously |

|

|

|

|

| B. Quality of work done |

|

|

|

|

| • … |

|

|

|

|

| Above average = Performance is above the expectations stated in the outcomes.

Average = Performance meets the expectations stated in the outcomes.

Needs improvement = Performance does not meet the expectations stated in the |

Rating scale example : Written report assessment

Expected learning outcome: The student will write a report that recommends one piece of equipment over another based on the pros and cons of each.

Criteria for success: All items must be rated as “Weak” or above.

| Report |

Unacceptable

0 |

Weak

2.5 |

Average

3 |

Good

4 |

Excellent

5 |

Weight |

Score |

| Introduction |

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

| Main Body |

|

|

|

5 |

|

|

|

| Summary |

|

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

| Total |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Easy Ways to Calculate Rating Scales!

Whether you’re creating a personality quiz, rating scales (aka Likert sales) are one of the best methods for collecting a broad range of opinions and behaviors.

In Cognito Forms, you can easily add either a predefined (Satisfied/Unsatisfied, Agree/Disagree, etc.) or completely custom rating scale to your form. Every question in a rating scale has an internal numerical value based on the number of rating options; for example, on a Good/Poor rating scale, Very Poor has a value of 1, while Very Good has a value of 5. You can reference these values to calculate scores, percentages, and more!

1. Total score

The easiest way to calculate a rating scale is to simply add up the total score. To do this, start by adding a Calculation field to your form, and make sure that it’s set to internal view only.

Next, target your individual rating scale questions by entering the name of your rating scale, the rating scale question, and “_Rating”:

=RatingScale.Question1_Rating + RatingScale.Question2_Rating + RatingScale.Question3_Rating

And that’s it! Now, the value of each question will be summed up:

If you want to display the total to your users, just insert the Calculation field into your form’s confirmation message or confirmation email using the Insert Field option:

2. Weighted score

Calculating a total score is simple enough, but there are a ton of other functions you can perform using rating scale values. For example, divide the rating scale total by the number of questions to calculate the average:

=(RatingScale.Question1_Rating + RatingScale.Question2_Rating + RatingScale.Question3_Rating) / 3

Or, if you have multiple rating scales, you can average each one and add them together:

=((RatingScale.Question1_Rating + RatingScale.Question2_Rating + RatingScale.Question3_Rating) / 3) + ((RatingScale2.Question1_Rating + RatingScale2.Question2_Rating + RatingScale2.Question3_Rating) / 3)

If you want the average of one rating scale to weigh more than another, just multiply each rating scale average by the percentage that it’s worth (in this case, 40%):

=(((RatingScale.Question1_Rating + RatingScale.Question2_Rating + RatingScale.Question3_Rating) / 3) *.4)

3. Percentages

Rather than displaying a total in points, you could also calculate a total percentage. To do this, add a Calculation field to your form, and set it to the Percent type. Next, write an expression that calculates the average of the rating scale divided by the number of possible options. For example, if your rating scale has three questions, and five options to choose from:

=((RatingScale.Question1_Rating + RatingScale.Question2_Rating + RatingScale.Question3_Rating) / 3) /5

Now, the total percentage will be calculated based on a 100 point scale:

Checklist for developing a rating scale

In developing your rating scale, use the following checklist.In developing a rating scale:

- Arrange the skills in a logical order, if you can.

- Ask for feedback from other instructors before using it with students.

- Clearly describe each skill.

- Determine the scale to use (words or words with numbers) to represent the levels of success.

- Highlight the critical steps, checkpoints, or indicators of success.

- List the categories of performance to be assessed, as needed

- Review the learning outcome and associated criteria for success.

- Review the rating scale for details and clarity. Format the scale.

- Write a description for the meaning of each point on the scale, as needed.

- Write clear instructions for the observer.

The Likert Scale: Advantages and Disadvantages

The Likert Scale is an ordinal psychometric measurement of attitudes, beliefs and opinions. In each question, a statement is presented in which a respondent must indicate a degree of agreement or disagreement in a multiple choice type format.

The advantageous side of the Likert Scale is that they are the most universal method for survey collection, therefore they are easily understood. The responses are easily quantifiable and subjective to computation of some mathematical analysis. Since it does not require the participant to provide a simple and concrete yes or no answer, it does not force the participant to take a stand on a particular topic, but allows them to respond in a degree of agreement; this makes question answering easier on the respondent. Also, the responses presented accommodate neutral or undecided feelings of participants. These responses are very easy to code when accumulating data since a single number represents the participant’s response. Likert surveys are also quick, efficient and inexpensive methods for data collection. They have high versatility and can be sent out through mail, over the internet, or given in person.

Attitudes of the population for one particular item in reality exist on a vast, multi-dimensional continuum. However, the Likert Scale is uni-dimensional and only gives 5-7 options of choice, and the space between each choice cannot possibly be equidistant. Therefore, it fails to measure the true attitudes of respondents. Also, it is not unlikely that peoples’ answers will be influences by previous questions, or will heavily concentrate on one response side (agree/disagree). Frequently, people avoid choosing the “extremes” options on the scale, because of the negative implications involved with “extremists”, even if an extreme choice would be the most accurate.

Critical Evaluation

Likert Scales have the advantage that they do not expect a simple yes / no answer from the respondent, but rather allow for degrees of opinion, and even no opinion at all. Therefore quantitative data is obtained, which means that the data can be analyzed with relative ease.

However, like all surveys, the validity of Likert Scale attitude measurement can be compromised due social desirability. This means that individuals may lie to put themselves in a positive light.

Offering anonymity on self-administered questionnaires should further reduce social pressure, and thus may likewise reduce social desirability bias. Paulhus (1984) found that more desirable personality characteristics were reported when people were asked to write their names, addresses and telephone numbers on their questionnaire than when they told not to put identifying information on the questionnaire.